Privacy, Surveillance and the Public

Evidence from SPIR 2023

Radhika Jha*

Even as the pros and cons of the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act 2023 continue to be debated, some important questions to be asked are—how does the Act tie in with the larger public’s awareness, opinions and expectations from the government on the right to privacy? Are these opinions and perceptions of the public founded on informed knowledge about the nuances of these debates? These are some of the issues that this article delves into, using data from the recently published ‘Status of Policing in India Report (SPIR) 2023: Surveillance and the Question of Privacy.’

The study, the fifth in the SPIR series of reports on policing in India, is brought out by Common Cause in collaboration with the Lokniti team of the Centre for Study of Developing Societies (CSDS). It includes, among other things, data from a survey of just under 10,000 people across 12 Indian states and UTs.

This article primarily relies on findings from the survey to bring out people’s lack of awareness on issues related to the right to privacy, coupled with some disturbing perceptions of the larger public on freedom of speech and right to dissent, to finally argue that the worst-affected when it comes to the violation of privacy are the already-vulnerable groups, particularly in the context of mass surveillance by the government.

One major criticism of the DPDP Act is regarding the wide exemptions granted to the state and its agencies for data collection and surveillance. Seen in this context, it can be argued that these exemptions can possibly exacerbate state surveillance of already marginalised groups, thus increasing their sense of vulnerability.

People’s Awareness Of Issues Related To Privacy

Even with a new legislation in place, the discourse around the right to privacy and data protection appears to have failed to permeate to the granular level of the common Indian person. There is not only a limited vocabulary to both comprehend and formulate the right to privacy at an individual, common person’s level on the one hand, but also an extremely limited level of awareness of national, and political debates related to these issues.

This lack of awareness, at least insofar as it relates to some current political events and debates on the

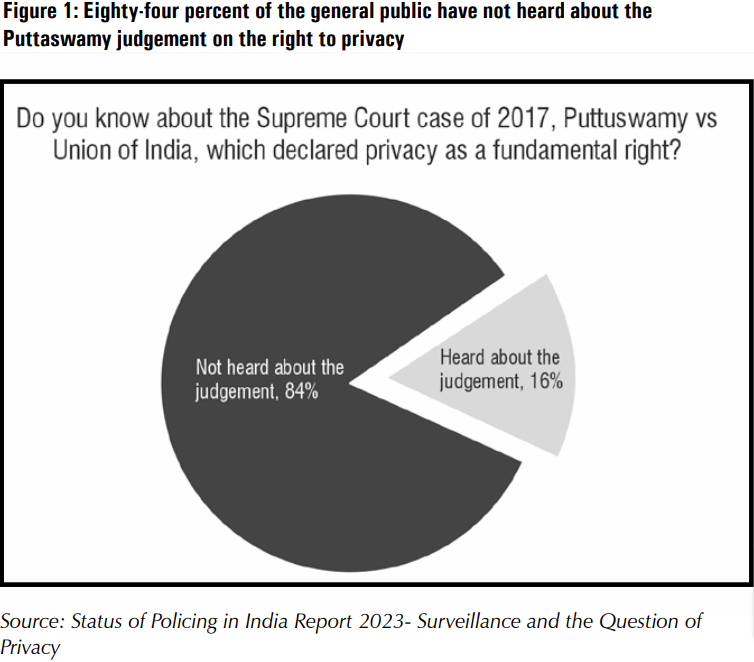

right to privacy, is evident from some of the survey findings of SPIR 2023. In 2017, the Supreme Court passed the landmark judgement on the right to privacy, declaring it a fundamental right for the people of India in Puttaswamy and Anr. v. Union of India and Ors. However, just a fraction of the 9,779 respondents, 16 percent, were aware of this judgement or had heard of it, while a staggering majority—eighty-four percent – were not aware of it.

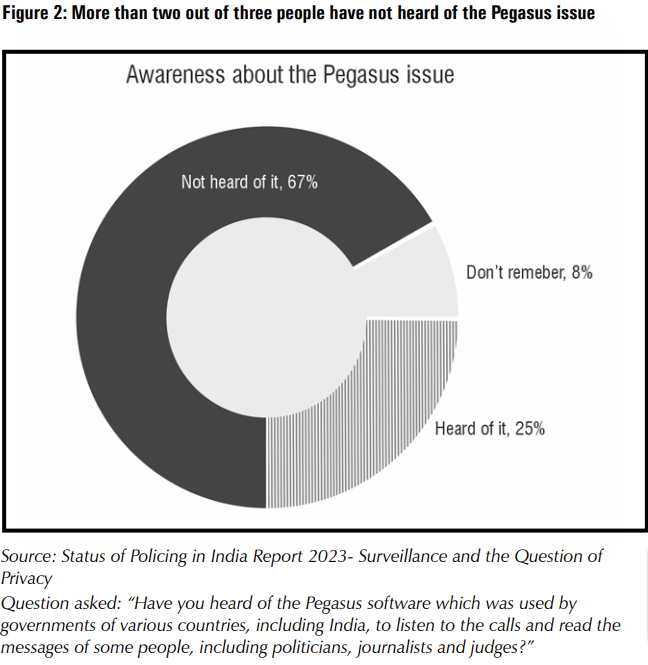

In July 2021, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalism (Pegasus project) revealed that about 50,000 phone numbers and linked devices across the globe were infected by the Pegasus spyware. It was alleged that several countries, including India, purchased the spyware from an Israeli company, the NSO Group, as part of their defence deals. In India, this spyware was allegedly used to target more than 300 people ranging from serving ministers and judges to journalists, activists and businesspersons (Shekar & Mehta, 2022).

This news, which led to a Supreme Court-appointed enquiry into the matter, created outrage amongst not just the political opposition but also in the media and amongst those advocating for free speech and the right to privacy. In this context, the general public was asked in the survey if they had heard of the Pegasus spyware issue. Again, a large majority—more than two out of three respondents (67%)—had not heard of the Pegasus scandal, while just one-fourth of the respondents (25%) had heard of it.

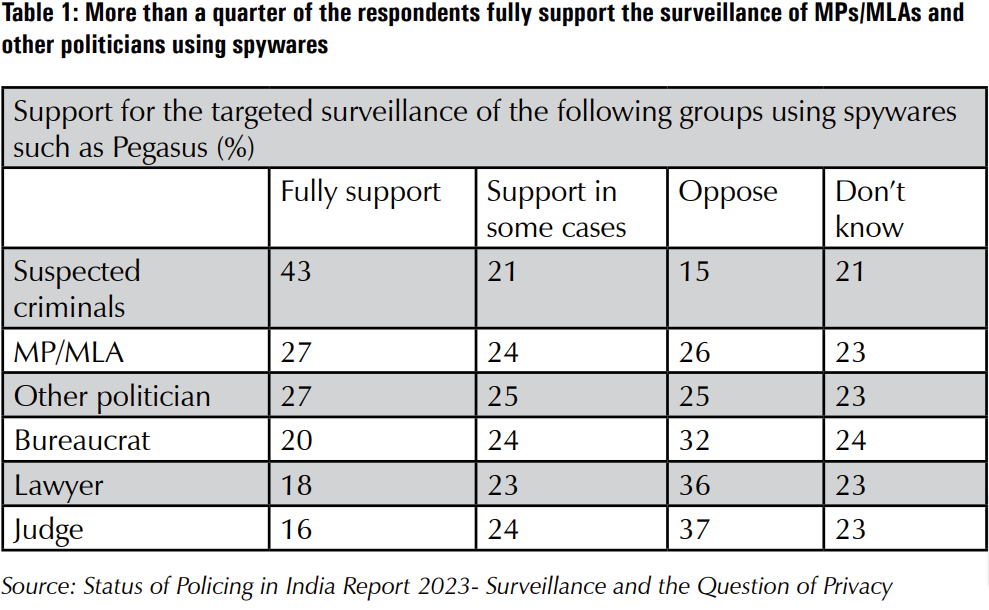

The low levels of awareness of the general public regarding issues such as the Pegasus scandal or the right to privacy judgment are coupled with dangerous opinions on the extent to which the government should carry out surveillance. While 43 percent of the respondents fully supported the use of such spyware by the government against suspected criminals, another 27 percent also fully supported its use against elected representatives such as MPs and MLAs, while 19 percent fully supported its use against journalists.

Whether or not these disturbing opinions are caused by the lack of awareness around the issue is debatable, but such opinions are completely contrary to the opinions of domain experts, some of whom were interviewed using a Focused Group Discussion (FGD) for the study. A group of 13 key informants, including former police officers, journalists, academics and civil society activists were interviewed using the FGD method. All of the FGD respondents were unanimous in their opinion that surveillance by the state can be used as an excuse to suppress dissent and silent opposition. While some FGD respondents

Question asked: “Should the government use Pegasus or similar software for phone hacking, location tracking etc. of these people, even if there is no criminal case against them?

- a. Journalist

- b. Judge

- c. Lawyer

- d. MP/MLA

- e. Other politicians

- f. Suspected criminals

- g. Ordinary citizens

- h. Businessman

- i. Bureaucrat

- j. NGO/social worker”

made the distinction between patently illegal activities such as hacking (under which spyware such as Pegasus would fall), and surveillance, they pointed out that targeted surveillance by the state can have a chilling effect on freedom of speech.

Freedom Of Speech And Right To Dissent

Regardless of whether the ignorance and lack of proper public discourse around the issues are directly related to some of the opinions on privacy,

surveillance and freedom of speech, the final picture that emerges from people’s perceptions is that of support for undemocratic, even illegal forms of surveillance that go against Constitutional values as well as judicial precedents on these matters. Thus, it may be argued, that there is little critical analysis of the new Act by the larger public, or enquiry into how the Act will play out in people’s daily lives and affect various sections of society.

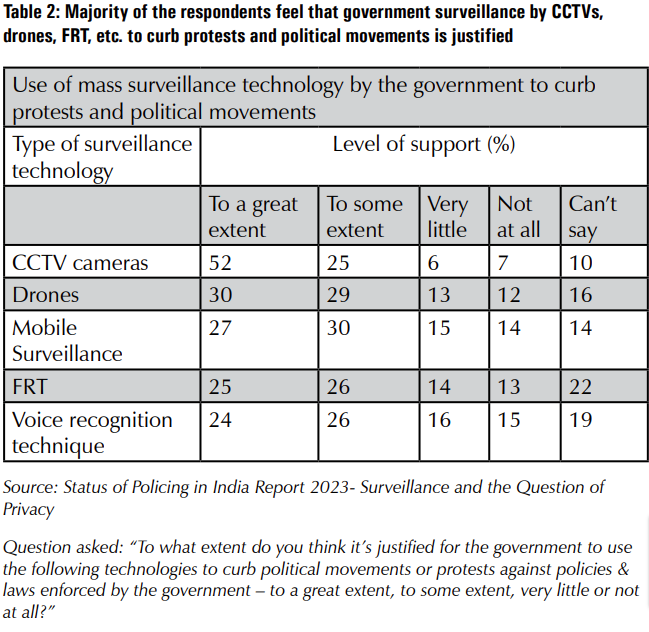

Some of the starkest examples of the support for extreme forms of surveillance, essentially gagging right to protest and freedom of speech, are given here using the survey findings. For instance, large sections feel that government surveillance by CCTVs (52%), drones (30%) and facial recognition technology (FRT- 25%) to curb protests and political movements is justified to a great extent.

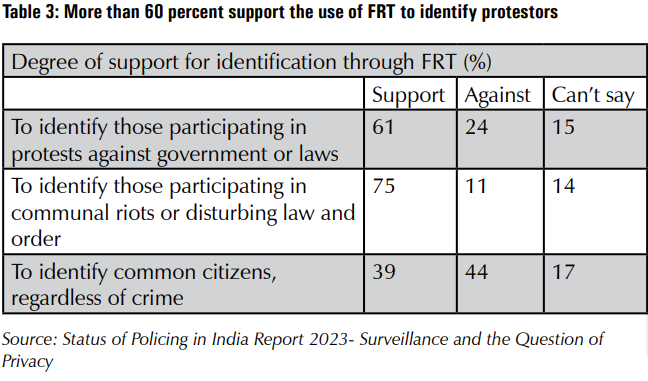

Similarly, 61 percent of the respondents support the use of FRT to identify those protesting against the government or its laws/policies. Even as leading international human rights organisations warn against the usage of technology to hinder peaceful protests and target protestors (OHCHR, 25th June 2020), there have been increasing reports of the use of such technologies to identify and target protestors (Reuters, February 17th, 2020). That such acts largely go unquestioned is explained by people’s support for such targeting, as revealed through this survey.

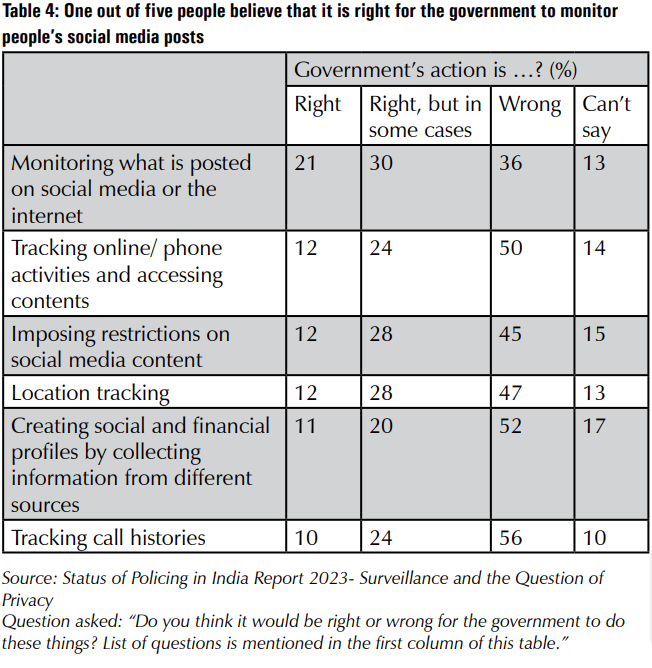

Another finding that attests to people’s lack of support for freedom of speech is that one out of five people believe that it is right for the government to monitor people’s social media posts, while another 30 percent feel that it is right only in some cases.

Question asked: “To what extent is the use of Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) by the police or the government justified in the following circumstances - to a great extent, to some extent, very little or not at all? (List of circumstances mentioned in the left column of the table).”

Note: The categories “to a great extent” and “to some extent” were clubbed together to make ‘support’ and ‘very little and not at all’ were clubbed to make ‘against’ for a better contrast. All figures are in percentages.

Impact on Vulnerable Groups

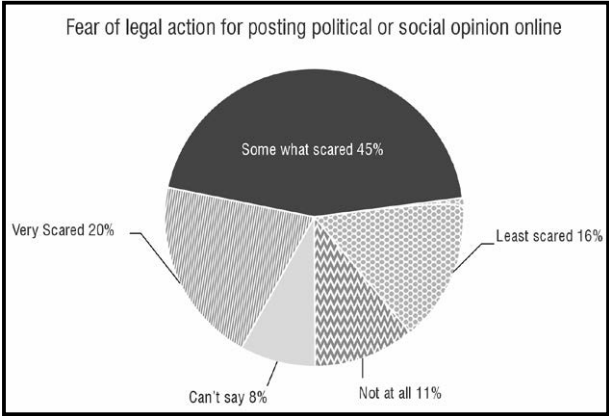

Even as the people, at least through their opinions and attitudes, grant license to the government to use surveillance technology to monitor and curb protests and dissenting opinions, they are also simultaneously afraid of voicing their own political and social opinions because of the fear of legal action. While 20 percent of people reported being very scared, another 45 percent were somewhat scared of legal action for posting their political or social opinion online.

Figure 3: Nearly two out of three respondents are scared to post their political or social opinions online for fear of legal action

Source: Status of Policing in India Report 2023- Surveillance and the Question of Privacy

Question asked: “How scared do you feel that if you post your opinions about a political or social issue on social media, and if it hurts the sentiments of certain groups, there might be legal action against you – very scared, somewhat scared, least scared or not at all scared?”

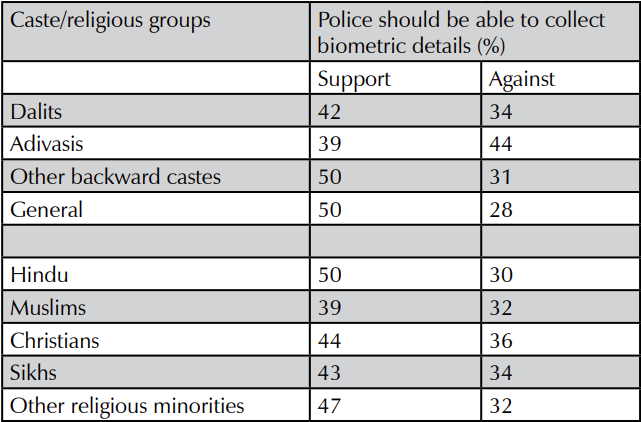

Table 5: Adivasis and Muslims are the most critical of the police collecting biometric details of all suspects

Source: Status of Policing in India Report 2023- Surveillance and the Question of Privacy

Question asked: “Do you think police should be able to collect the biometric details (such as fingerprint, footprint, iris, retina scan, facial recognition, etc.) of all suspects, including those who haven’t been declared guilty by the court?” Note: Rest did not respond.

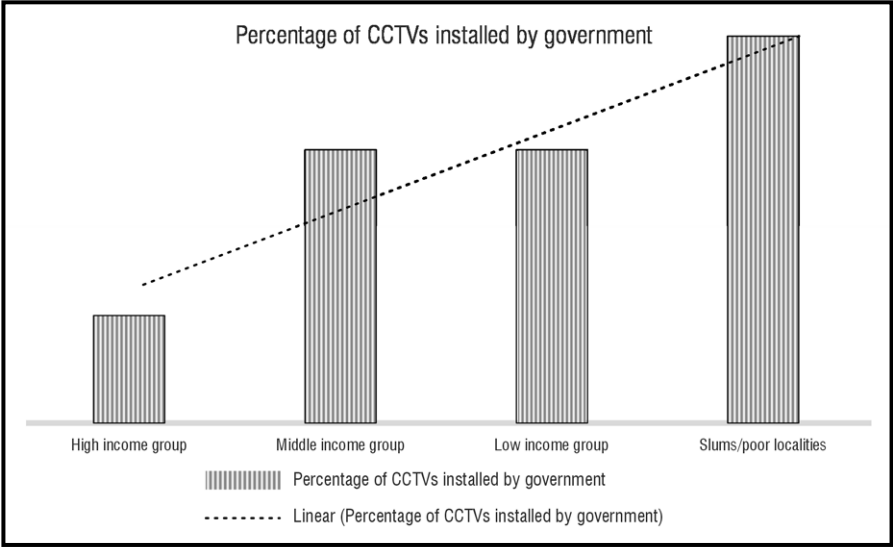

Figure 4: The government is three times more likely to install CCTV cameras in slums/poor localities, compared to higher-income localities

Source: Status of Policing in India Report 2023- Surveillance and the Question of Privacy

Note: All figures are in percentages. Data of only those respondents who reported having CCTV cameras in their households/ residential areas.

Question asked: “Were CCTVs installed by you or some other authority?”

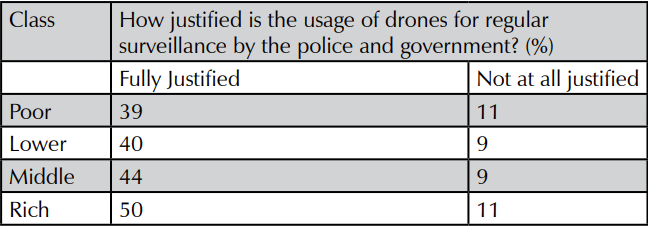

Table 6: Poor least likely to support regular drone surveillance of the public by the police/government

Source: Status of Policing in India Report 2023- Surveillance and the Question of Privacy

Note: All figures are in percentages. Extreme polarities were taken into consideration rather than moderate categories on either side while analysing to give a clear distinction of choices.

Question asked: “In your opinion, to what extent is the use of drones justified for regular surveillance of the public by the government or police?”

(Identification) Act, 2022 which authorises police to collect biometric details of all persons who have been apprehended by them, whether as an accused, convict or otherwise.

Another example of the differential impact on vulnerable sections of society emerges from the finding that although the poorest are least likely to support the installation of CCTV at any location, the government is three times more likely to install CCTV cameras in slums/poor localities, compared to high-income localities.

Similarly, respondents from the poor and lower class are also least likely to support the use of technologies such as drones by the police and government for regular surveillance. While 50 percent of the rich respondents said that the use of drones by the government and police for regular surveillance of the public was fully justified, notably lower 39 and 40 percent of the poor and lower-class respondents respectively agreed.

Conclusion

The above are only some of the findings that point to the differential impact of state surveillance on marginalised groups, and the increased sense of vulnerability amongst these sections of the society. Even as there is a limited understanding of the nuances of surveillance technology, state surveillance and issues related to data protection and the right to privacy, there is an apparent distrust and wariness amongst the already vulnerable groups of such surveillance by the state.

Some of the findings of the latest SPIR provide an insight into why there is little public engagement and debate on not just the new legislation, but issues surrounding the right to privacy and data protection in general. While on the one hand there is a lack of awareness about some of the current political happenings in the context of privacy and surveillance and India, on the other, people in general tend to hold strong opinions supporting the use of surveillance to curb protest and dissent, which often run contrary to democratic values on the freedom of speech and expression. However, when the responses of the public on these issues are sliced across religious, caste and class lines it emerges that it is the marginalised groups who are most critical of such surveillance by the government.

In this context, the exemptions under the Act, which allow the state to collect data under broad conditions, such as security of the state, preservation of public order, prevention of offences and incitement to commit offences, provide wide discretion to the state and can potentially increase the sense of vulnerability and fear amongst the marginalised groups, defeating the purpose of “protection” under the new Data Protection Act.

References

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) (25th June 2020). New Technologies Must Serve, Not Hinder, Right to Peaceful Protest, Bachelet Tells States. Geneva. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3rH9bM

- Shekar, K., & Mehta, S. (17th February 2022). The State of Surveillance in India: National Security at the Cost of Privacy? Observer Research Foundation. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3txdUkR

- Siddiqui, Z. & Ulmer, A. (17th February 2020). India’s Use of Facial Recognition Tech During Protests Causes Stir. Mumbai/New Delhi, India. Reuters. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3ZSLIoq