Can Education be Left to Market Forces?

Real Improvement Needed in Teaching-learning Quality

Anita Rampal*

Soon after the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 was approved in the throes of the pandemic, without a parliamentary debate, an equally sudden promulgation of the Odisha Universities Ordinance 2020 (No. 12, to amend the Odisha Universities Act 1989) has alarmed the academic community.

In a federal structure with education as a concurrent subject, states have a role in making their policies. An unprecedented measure in centralised educational governance was first put forward by the draft NEP (2019) for a permanent apex Rashtriya Shiksha Ayog (National Education Commission), chaired by the Prime Minister (later the education minister, in a subsequent draft).

Fortunately, after much opposition from the states as well as legal experts resulted in the measure being dropped just before the final policy was put out. The NEP has recommended central control through resetting the agendas of existing national bodies and the proposed setting up of new ones, such as the National Research Fund, the National Assessment Centre (PARAKH), the National Educational Technology Forum or the Higher Education Commission of India (with multiple vertical structures of authority).

Some states have expressed concerns and are still assessing its implications. Instead of resisting greater control on its educational institutions, the Odisha University Ordinance is vying with the centre to wrest more political and bureaucratic power. It removes the role of the Vice Chancellor in the appointment of faculty and non-teaching staff, now to be done through the State Public Service Commission and the State Selection Board respectively. It abolishes the senate which serves as an academic council and rests all decision making on the syndicate, with government nominees. It also mandates the Chancellor to nominate a retired bureaucrat instead of an academic in the search committee for a Vice Chancellor. Stifling universities under greater state control does not bode well for academic credibility and has been seen to result in mediocrity and irreparable decline. Claims of ‘autonomy’ made in the NEP need deeper scrutiny within its plan of creating a hierarchy of institutions, with implications for access to resources. Some of the best colleges of Delhi University have resisted the offer of ‘autonomous’ status, seen as a euphemism for having to fend for their own funds, and also raise fees. Teachers have also seen this as a move that isolates an institution from the larger network of affiliated colleges, which provides a collective resource for academic matters of

curriculum and administrative issues that need redress on a larger forum. With already an acute shortage of qualified teachers in the system and almost half of them being ad hoc or contractual appointments, the policy rhetoric of a robust culture of autonomous and motivated teaching faculty fails to convince.

Student groups have engaged with the disparate realities of their lives, mobilised against growing commercialisation of education and resisted crippling fee hikes.

The precarity of teaching will increase owing to a tenure track, a five year or longer probation, multiple levels of a salary scale, performance appraisals through peer, student and even community reviews, and modular on-line courses for professional development.

One cannot help but look at what is happening to our best universities with the most eminent and committed teachers constrained by hostile administrations and centralised fiats.

Those who work for social justice and question government policies face unprecedented threats for being ‘anti-national’ and are even being falsely charged for terrorist and unlawful activities (Mehta, 2020). One needs to be repeatedly reminded of the founding vision, for the need of democracy and autonomy in higher education, as posited by the first University Education Commission (1948-49). Chaired by Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, it warned that state funding was not state control. “Freedom of individual development is the basis of democracy. Exclusive control of education by the State has been an important factor in facilitating the maintenance of totalitarian tyrannies. ....We must resist, in the interests of our own democracy, the trend towards the governmental domination of the educational process.... Professional integrity requires that teachers should be as free to speak on controversial issues as any other citizens of a free country. An atmosphere of freedom is essential for developing this ‘morality of the mind.’”1 The Radhakrishnan Education Commission, as it is popularly known, envisioned universities as ‘homes of intellectual adventure.’ It also viewed autonomy as a responsibility of the state to protect democracy, and promote knowledge creation for social justice, “which demands the freeing of the individual from poverty, unemployment, malnutrition and ignorance. This is not enough. We must cultivate the art of human relationships, the ability to live and work together overcoming the dividing forces of the time.” Acknowledging the role of education in perpetuating status quo, it warned that the aim must not be to produce conformist citizens to adjust to given social norms, but individuals who can bring social change to uphold the Constitution.

It asserted that education is a universal right, not a class privilege. The report cited the example of the legendary mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan, from Jawaharlal Nehru’s The Discovery of India. It emphasised that when basic conditions of health, education and opportunities of growth were available for all, many among the millions living on the verge of starvation would become eminent scientists, educationists, technicians, industrialists, writers and artists, to help build a new India and a new world.

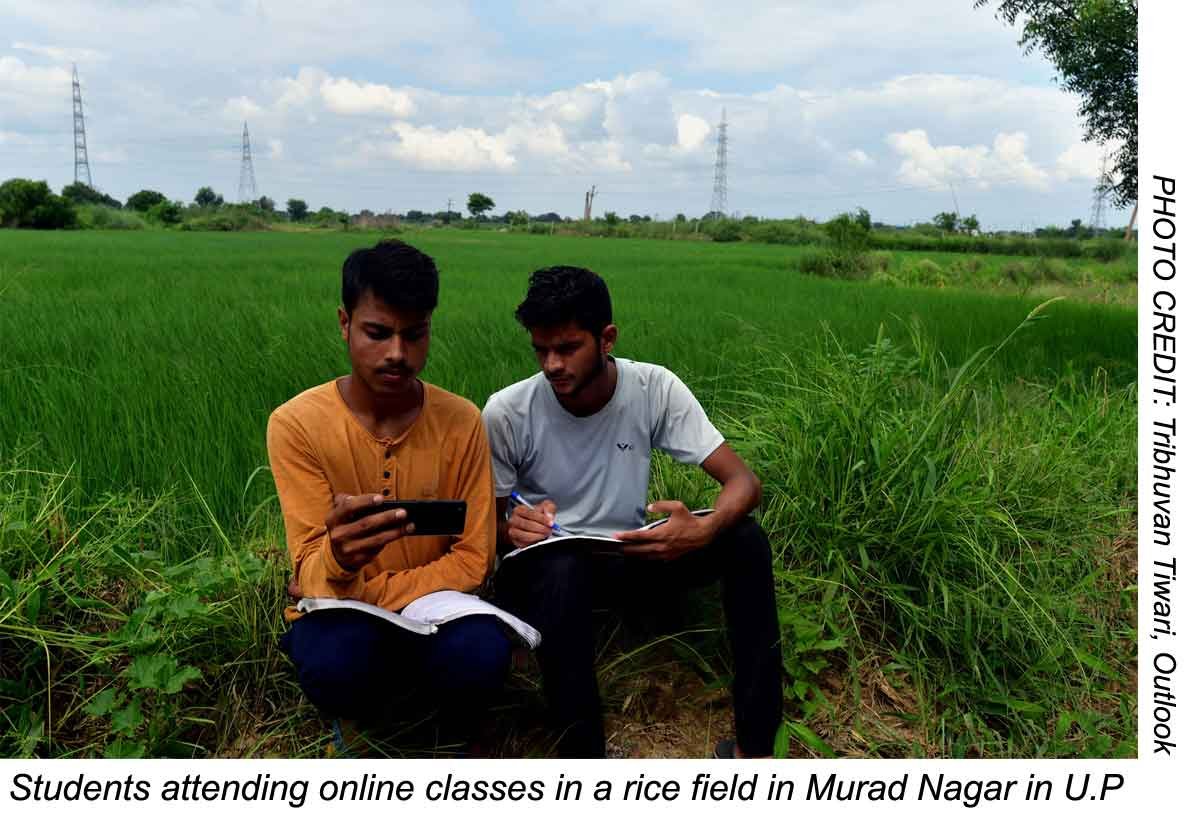

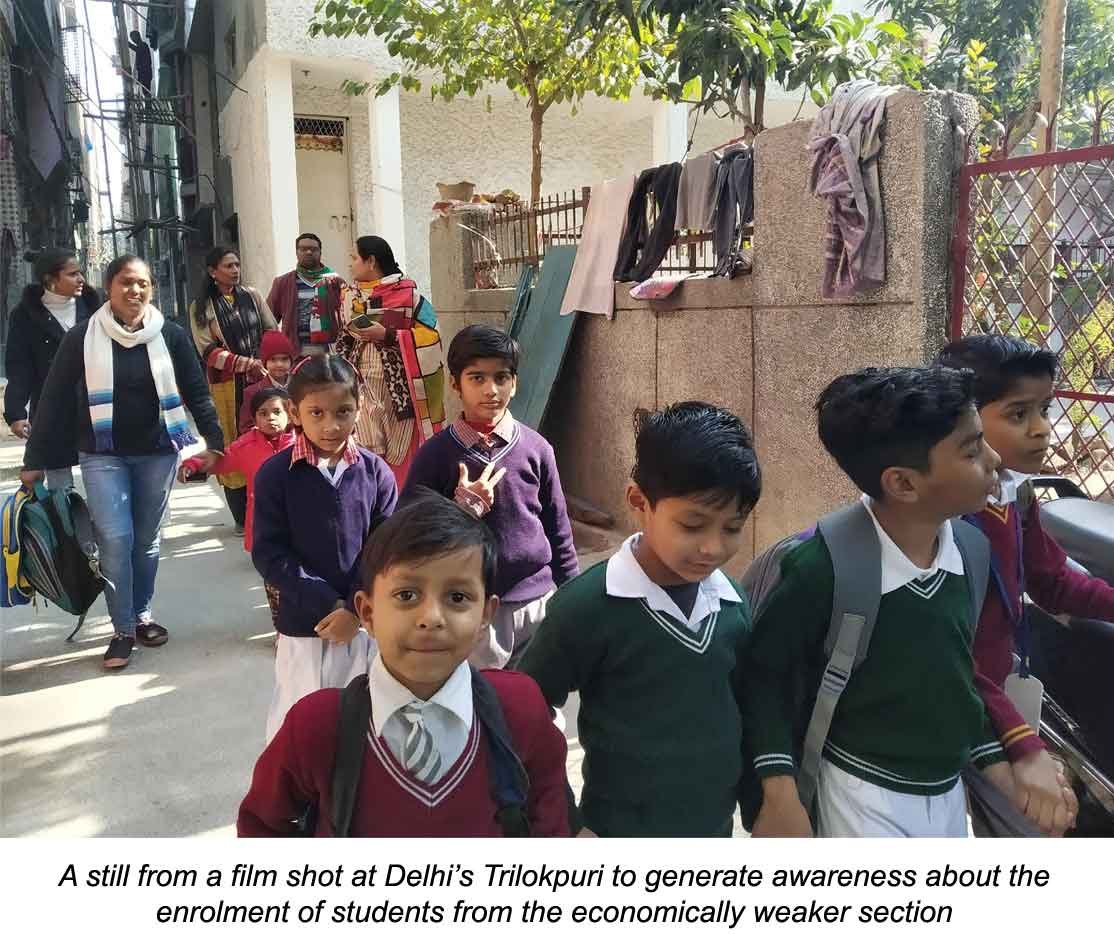

With affirmative action in terms of reservations, a demographic change has been witnessed in public universities which serve as a democratic site to students from diverse social backgrounds aspiring for higher education.2 These are also places where students and teachers can challenge the present dystopian market forces (Rampal, 2018) dismembering education from its essential discourse of democracy, social responsibility and civic courage.3 Student groups have engaged with the disparate realities of their lives, mobilised against growing commercialisation and commodification of education, resisted crippling fee hikes, and protested against gender, caste and religious discrimination. However, the growing aspirations of students for good quality public education are not met while students from disadvantaged and deprived groups are increasingly being channelled into avenues of open and distance learning (ODL). This is in no way comparable to the social processes of regular education. However, the NEP abandons a commitment to expand good quality public education, stating that ODL and online education will provide the ‘natural path’ to increase access to quality higher education.

Following market principles of economies of scale, the policy proposes a college to have over 3000 students (though the All India Survey of Higher Education in 2019 showed only 4 percent colleges in this category), and a university with over 25000.

Contrary to the discourse of ‘choice’ and ‘flexibility,’ our system continues to sort and select, based on students’ social capital that constructs their ‘ability’ or ‘merit’ to perform and pay.

It also justifies closure and merger of suboptimal schools and establishing school complexes. In college it legitimises exit at each year of an undergraduate course. In addition, without scrutinising the complexity of equivalence of institutions it proposes a credit bank so that students can return or migrate at will.

Moreover, increasing enrolments is tied with its aim to channelise half of all students at school and college into vocational education, which unfortunately, has very little education, mostly skills designed by the industry. It serves as second rate stream for the so called ‘low ability’ students to be prepared for low-status employment. In school education, the policy crafts a semantic space for ‘public philanthropic partnership.’ It assures that there will be no focus on inputs, but instead, a substantial loosening of the ‘restrictive’ requirements of the Right to Education (RTE) Act. Children of age 6-14 years have a right to good quality free and compulsory education in a neighbourhood school till completion of elementary education. RTE lays down the nature of education for building up the child’s knowledge, potentiality and talent; learning through activities, discovery and exploration in a child friendly manner. The aim of that education is to make the child free of fear, trauma and anxiety and help him/her to express views freely (clause 29).

NEP contradicts RTE when it regresses to provide ‘universal access,’ but does not ensure completion as a right. More damagingly, it compromises with quality and calls for ‘alternative models’, through ‘multiple pathways’ which include non-formal and open schooling even at grades 3, 5 and 8. Its Foundational Literacy and Numeracy Stage (age 3-8 years), combining three years of Early Childhood Care and Education (age 3-6 years in anganwadis) and grades 1 and 2 of school, offers a minimalist curriculum. Worryingly, along with anganwadi workers, who are not professionally trained teachers, it opens the space to volunteers, community members and also child-tutors from the same school. Not only is the term ‘tutoring’ out of place in a national policy, making young children ‘tutor’ others is violative of their rights.

Its focus on state examinations [guided by the National Accreditation Council (NAC)] even in grades 3, 5 and 8, runs contrary to the RTE, which disallows children to be subjected to a board examination, allowing only regular school examinations. Similarly, its requirement that the essential core curricular content will be decided at a national level, while state textbooks add local context and flavour, problematically impinges upon the states’ constitutional role to develop their own curricula.

Contrary to the discourse of ‘choice’ and ‘flexibility,’ our system continues to sort and select, based on students’ social capital that constructs their ‘ability’ or ‘merit’ to perform and pay. The vocationalist instrumental view of education in the NEP, based on metrics of outcomes, denying inputs crucial for the disadvantaged, will further push students, teachers and institutions into an aggressive race for rankings and survival. Negotiating renewed hierarchies of skill and knowledge, or regular and distant modes, through centrally calibrated norms, such systems of education will expunge vestiges of equity and justice from its notion of ‘quality.’ Significantly, every mention of constitutional values in the NEP is prefaced by ethical or human values, so that in a long list of 30 or more, the more mundane ‘respect for public property’ or cleanliness can precede equality or justice, which invariably lie at the end, while secularism is conspicuously missing.

*Anita Rampal is professor and former dean of the Faculty of Education at Delhi University

( References )

- (1) Rampal, Anita. (2020) The NEP Goes Against the Existing Constitutional Mandate of the RTE. The Wire. Retrieved October 20,2020 from https://bit.ly/3j9BDwo

- (2) Mehta, Pratap Bhanu (2020, September 25) You Dare Not Speak. The Indian Express. Retrieved October 20,2020 from https://bit.ly/34eVIx1

( Endnotes )

- (1) The Report of the University Education Commission (1950). Ministry of Education, Government of India

- (2) Deshpande, Satish (2016, March 12) The Public University after Rohit-Kanhaiya. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. LI No. 11, Issue No. 32-34. Retrieved October 20,2020 from https://bit.ly/31rAnyD

- (3) Rampal, Anita (2018) Manufacturing Crisis: The Business of Learning. Seminar, The Crisis in Learning, Vol. 706, June, 2018, p55-59. Retrieved October 20, 2020 from https://bit.ly/2Hh7EFV

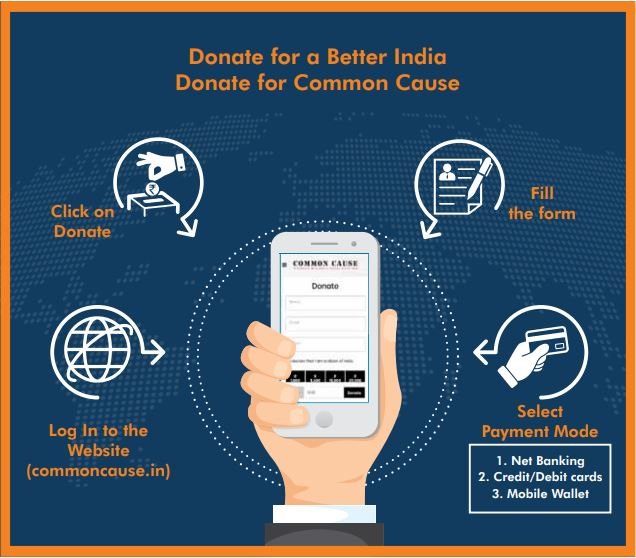

Common Cause is in the vanguard of India’s anti-corruption movement and the fight for stronger public institutions since the 1980s. We make democratic interventions through PILs and bold initiatives. Our landmark PILs include those for the cancellation of 2G licenses and captive coal block allocations, against the criminalisation of politics, for Internet freedom and patients’ right to die with dignity. Please visit commoncause.in for more information on our mission and objectives. We also run special programmes on police reforms and cleaner elections. Common Cause runs mainly on donations and contributions from well-wishers. Your support enables us to research and pursue more ideas for a better India. Now you can also donate using our new payment gateway.

NEXT »

Gaps in Teachers' Training >>

By Poonam Batra