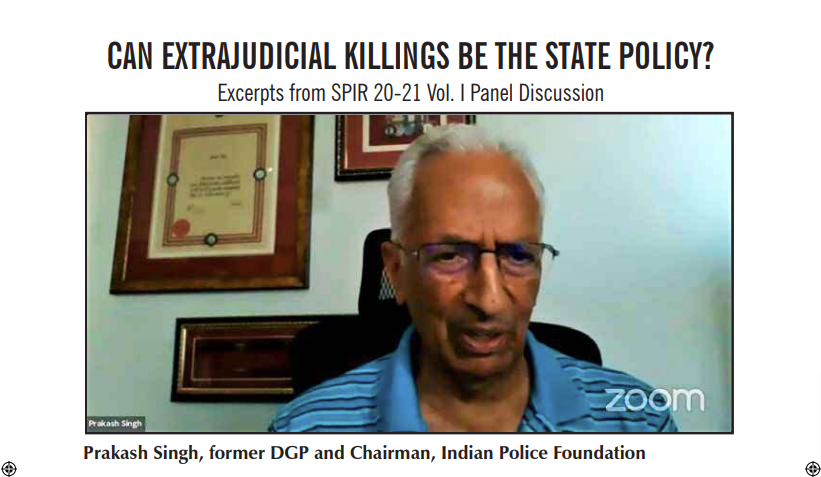

Panel Discussion: Prakash Singh, Former DGP

On complaints against the police: A history

The subject of today’s discussion is, ‘Can Extrajudicial Killings be the State Policy?’ Well, the answer is an obvious, no. Historically, the National Police Commission (NPC), in its very first report, published in 1979, said that there are certain complaints against the police, which must mandatorily be subjected to judicial inquiry. They mentioned specifically that in any instance of death of two or more persons resulting from police firing, a judicial inquiry must be held. Subsequently, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) issued some guidelines in 1997 and then followed that up in 2010.

They said that for all cases of deaths in police action FIRs must be registered, magisterial enquiry must be held, report sent to the NHRC within 48 hours of their occurrence. This should be followed by a subsequent report along with Post-mortem and Inquest reports as well as findings of the magisterial inquiry/inquiry by senior officers within three months. But what should be followed at the ground level today is the SC guidelines given in 2014 by then Chief Justice RM Lodha and Justice Rohinton Fali Nariman. They laid down 16 points, which must be followed in all cases of police firing resulting in deaths. The guidelines state that FIRs must be registered and cases investigated by the CID or police team of another police station under the supervision of a senior officer at least a level above the head of the police party engaged in the encounter. This should be followed by a magisterial inquiry. Also, six-monthly statements of all cases where deaths have occurred in police firing must be sent to NHRC by DGPs. In addition, the officer who was involved in firing must surrender his weapon for ballistic examination, and should not be given any promotion or gallantry medal until the case has finally been decided and cleared. These 16-point guidelines, issued by the SC in 2014, are generally being followed by the state governments.

On extra-judicial killings

Now, these principles are unexceptionable and must be followed. Then, why are we discussing this topic today? Because there are so many extra-judicial killings or fake encounters. In the Telangana encounter of December 6, 2019, four alleged rapists were bumped off by the police. What followed was popular support, approval, and endorsement by not only the people, but also the government. That caused a lot of discomfort among thinking people. They contemplated on how the entire society and even the governmental machinery can support such an encounter.

While criticising the Telangana encounter, we also need to think seriously. Going back in history, there were the Bhagalpur blindings. How is it that society comes out in support of such brutal acts of blindings or killings en masse? After all, these people are not mad. Therefore, we need to figure out what is wrong, identify and address it. When people express their endorsement of such extra-judicial killings, they are indirectly conveying that there is zero faith in the criminal justice system of the country. They are sceptical about whether these men would be brought to justice, whether they would ever be punished or whether the case would drag on for 10 years, 20 years or 30 years. At the end of the long legal process, witnesses turn hostile, some of them die and the criminal ultimately has the last laugh. It is the failure of the criminal justice system to deal with the mafiosi and dreaded criminals who have the capacity to influence witnesses, proceedings, and even judges. This was confided to me by a CM of an important state who had a problem handling a mafioso. That is why there is a general approval when such extra-judicial killings take place.

I am not at all condoning these killings, nor am I justifying them. I am merely emphasising that the criminal justice system must become functional. It must deliver within a short span of time and not drag on like the case of postal worker Umakant Mishra, who was cleared by court after 29 years. That is a problem. The criminal justice system is not delivering. It must deliver for such killings to stop getting the approval from society.

On policing in insurgency and terrorism affected areas

There is another area which also needs attention. On one hand rapists and history-sheeters like Vikas Dubey are killed in the domain of normal policing. But it is a different story in areas affected by insurgency and terrorism. After the battle against terrorism was won in Punjab, 2,500 writ petitions were filed in the Punjab and Haryana HC and SC against the Punjab police personnel. Now, imagine the plight of the police personnel who were in the forefront of the battle. I am saying this from my personal experience because I was there in Punjab when the state was burning.

The only department functioning in the state was the police. Lending support was the paramilitary, aided by the army, who fought the terrorists. All the other departments had become dysfunctional. Even the judiciary was not functioning. There were a number of stories about judges being brow-beaten and bullied inside the court premises by the terrorists. In such a situation, the Punjab police fought the battle but at the end of it, they faced more than 2000 writ petitions. Several police personnel, including one SP committed suicide. Journalist Shekhar Gupta wrote about these writ petitions. He said “It is perfectly valid to question the methods used by the security forces. But is it not more important to ask who is ordering them to do so? It is incredibly and shamefully low of us to ask our own forces to put their lives on the line, do the dirty work, and then when all is back to normal and the debris of war is cremated and

When people express their endorsement of extra-judicial killings, they are indirectly conveying that there is zero faith in the criminal justice system of the country.

The criminal justice system is not delivering. It must deliver for extrajudicial killings to stop getting the approval from society.

buried to harp back to the law is supreme, in a civil society mode. The Punjab crisis saw 5 Prime Ministers and as many internal security ministers. Each one knew precisely what was going on. Why are they hiding now? Why are they not being charged with genocide?”

I was in Punjab from 1987- 1991. Any leader or top-level government functionary touring Punjab at that time had one simple message for all of us: ‘Do what you like, but finish terror.’ And then former Union minister Arun Shourie also wrote: “Society, of course, will have to consider a fundamental point that goes beyond mere law. To ask a person to fight at the risk of his life on certain terms and conditions and later when the man has saved the day for society, to turn around and say sorry, these conditions we promised you are not constitutional. What is that, but the worst sort of breach of faith?” Why should anyone risk his life to protect such a society?

I concede that in insurgency/ terrorist situations, things do go wrong at times. I think the test should be whether the mistakes or killings happened in the bonafide discharge of duties, or whether they were cold-blooded killings and staged encounters. I think we need to draw a line. Once you find out that it was a cold-blooded killing and people were collected at a place and then shot down, then those cases do not have to be condoned. But there are cases which come in the category of ‘collateral damage.’ I have seen that when you’re facing a group of determined Maoists in Maoist affected areas, and opening fire, the possibility of some villagers getting killed in the process is always there. Now, what do you do? Just allow yourself and your men to be killed or just take them head on? So, while human rights are very important, when you are fighting a group of terrorists/insurgents, sometimes there would be unintended casualties. If it happens in the bonafide discharge of duties then we’ll have to take a different route. But on the other hand, I know of instances where coldblooded killings happen, and those need not be condoned.

On global views on policing

In this context, let me bring to your notice the UK experience. The Defence Secretary of Britain admitted in a statement made in October 2016 that “Our legal system has been abused to level false charges against our troops on an industrial scale.” He added that this has “caused significant distress to people who risked their lives to protect us.” The statement was made in the context of claims over alleged humans rights abuses committed by the British troops in Afghanistan and Iraq. Let us also look at the European Convention on Human Rights. Article 15 of the European Convention on Human Rights says, “In time of war or other public emergency threatening the life of the nation any High Contracting Party may take measures derogating from its obligations under this Convention to the extent strictly required by the exigencies of the situation, provided that such measures are not inconsistent with its other obligations under international law.”

English judge Lord Denning once said: “When the state is endangered, our cherished freedoms may have to take a second place”. I have spent more than 12 years in terrorist and insurgency affected areas and these are the dilemmas we face. I can assure you that I never faced any accusations of human rights violations in any of the theatres I operated in. And there were instances where people got killed. But my instructions to the men were very clear: ‘So long as you are acting in the bonafide discharge of your duties, I shall defend you.’ But there were also instances when they had transgressed the limits of law. Then I told them that before the government hangs you, I will be the first person to punish you.

NEXT »