Information Commissions on Deathbeds?

A Report Card Paints a Dismal Picture

October 16, 2021, marked 16 years since the implementation of the Right to Information Act, 2005 or the RTI Act. Paying tribute to the occasion, Satark Nagrik Sangathan (SNS), a citizen’s group working to promote transparency and accountability in government functioning, came out with the study ‘Report Card on the Performance of Information Commissions in India, 2021.’ This report is part of an ongoing series of assessments on various aspects of the implementation of the RTI Act in India. The aim of the exercise is to improve the functioning of information commissions and strengthen the RTI regime in the country.

The report is primarily based on an analysis of information accessed under the RTI Act, from 29 information commissions across India. A total of 156 RTI applications were filed with state information commissions (SIC) and the Central Information Commission (CIC). The information sought included:

The number of commissioners serving in each commission for the period August 1, 2020, till June 30, 2021, and their backgrounds, as well as the number of appeals and complaints registered, disposed of, returned by each IC for the period August 1, 2020, till June 30, 2021. Details were also sought for the number of appeals and complaints pending before each IC on December 31, 2020, March 31, 2021, and June 30, 2021, the quantum of penalties imposed by each IC, and the amount recovered, for the period August 1, 2020, till June 30, 2021. Finally, enquiries were made on the quantum of compensation awarded by each IC, for the period August 1, 2020, till June 30, 2021, the number of cases in which disciplinary action was recommended by each IC and the latest year for which the Annual Report of the IC has been published.

It is important to note that the report largely covers the duration in which the majority of citizens, especially the marginalised and poor of the country, witnessed the devastating impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. The severe lockdown imposed owing to the health emergency brought to a sudden halt all economic activities and eventually increased the dependency of the poor on government-sponsored welfare schemes. In such a scenario, transparent functioning of relief work and timely access to relevant information became even more important. Through the assessment of the information commissions during these testing times, the report adds clarity to the functioning of the commissions, their limitations, challenges and the overall status of the RTI Act in the country.

The report details how each RTI application was tracked to assess the manner in which it was dealt with by the ICs, as these bodies are public authorities under the RTI Act. In addition, information has also been sourced from the websites and annual reports of information commissions. The report also draws on findings and discussions that were a part of previous national assessments of the RTI regime, carried out by outfits such as the Research, Assessment, & Analysis Group (RaaG), Satark Nagrik Sangathan (SNS) and Centre for Equity Studies (CES). Some of the edited key findings from the report are given here:

1. Vacancies in information commission:

Under the RTI Act, information commissions consist of a chief information commissioner and up to 10 information commissioners, appointed by the President of India at the central level and the governor in the states.

The report found that several ICs were non-functional or were functioning at reduced capacity as the posts of commissioners, including that of the chief information commissioner, were vacant during the period under review. This was particularly concerning as the humanitarian crisis induced by the Covid-19 pandemic had made the poor and marginalised people even more dependent on government provisions of essential goods and services like healthcare, food and social security. Without access to relevant information, it is difficult for citizens to exercise their rights and claim their entitlements, leading to corruption.

1.1 Non-functional information commissions:

The report found four information commissions non-functional for varying lengths of time for the period under review as all posts of commissioners were vacant. Three commissions were found to be completely defunct at the time of publication of this report. In the absence of functional commissions, information seekers have no reprieve under the RTI Act, if they are unable to access information as per the provisions of the law.

Jharkhand: The Chief Information Commissioner of the Jharkhand State Information Commission (SIC), demitted office in November 2019. Subsequently the lone information commissioner was also made the acting Chief, although no such explicit provision exists under the RTI Act. However, upon the completion of the tenure of the commissioner on May 8, 2020, the information commission has been without any commissioner, effectively rendering it completely defunct.

Tripura: The information commission of Tripura became defunct on July 13, 2021 when the sole commissioner, who was the Chief, finished his tenure. Since April 2019, this is the third time the commission has become defunct. It was defunct from April 2019 to September 2019, then from April 2020 to July 2020, and now again since July 13, 2021.

Meghalaya: The information commission of Meghalaya became defunct on February 28, 2021 when the only commissioner, who was the Chief, finished his tenure. Since the last seven months, the government has not made a single appointment.

Goa: The information commission of Goa was defunct for over a month when the lone commissioner, who was also officiating as the Chief, finished her tenure on December 31, 2020.

1.2 Commissions functioning without a Chief Information Commissioner:

Currently, in three information commissions in the country all posts of information commissioners, including that of the Chief, are vacant and another three commissions are functioning without a Chief Information Commissioner.

Central Information Commission: The Central Information Commission (CIC) was without a Chief for a period of two months when the then Chief demitted office on August 26, 2020 after completing his tenure. This was the fifth time in seven years that the CIC was rendered headless due to the delay in appointing a new chief upon the incumbent demitting office.

Manipur: The SIC of Manipur has been functioning without a Chief for 31 months, since February 2019. While one of the commissioners has been given charge as the Chief Commissioner, no such legal provision exists in the law.

Nagaland: The SIC of Nagaland has been functioning without a Chief since January 2020, i.e., a period of 21 months.

Telangana: The state information commission was constituted in 2017. The Chief demitted office in August 2020 and since then an existing commissioner is functioning with the additional charge of the Chief, though there is no such explicit provision in the law.

Uttar Pradesh: The SIC of UP was headless for a period of one year from February 2020 to February 2021. Through the first lockdown in 2020, when important decisions regarding management of the affairs of the commission were to be taken, a role envisaged for the Chief as per the RTI Act, the commission was without a chief.

Rajasthan: The Chief of the Rajasthan Commission demitted office in December 2018, and the commission was without a Chief till December 2020 i.e., a period of two years.

Kerala: The SIC of Kerala was without a Chief for more than three months when the previous Chief demitted office in November 2020. The new Chief was appointed in March 2021.

1.3 Commissions Functioning at Reduced Capacity:

Under the RTI Act, information commissions consist of a chief information commissioner and up to 10 information commissioners. Several information commissions have been functioning at reduced capacity. The non-appointment of commissioners in the ICs in a timely manner leads to a large build-up of pending appeals and complaints.

Central Information Commission: In December 2019, when there were four vacancies in the CIC, the Supreme Court had directed the central government to fill all vacancies within a period of three months. However, the government did not comply and appointed only one new commissioner and elevated an existing commissioner to the post of Chief. By September 2020, the Chief and another commissioner finished their tenure and a total of six posts, including that of the Chief, fell vacant. In November 2020, three new commissioners were appointed and an existing commissioner was made the Chief, bringing the number of vacant posts to three. The backlog of appeals/complaints has been steadily increasing and currently stands at nearly 36,800 cases.

Maharashtra: The SIC of Maharashtra has been functioning with just four information commissioners, including the Chief, for the past several months. Due to the commission functioning at a severely reduced strength, the number of pending appeals/complaints has risen at an alarming rate. While as of March 31, 2019, close to 46,000 appeals and complaints were pending, the backlog as of December 2020 increased to around 63,000 and reached an alarming level of nearly 75,000 by May 2021.

Karnataka: While the SIC has failed to provide the number of pending appeals/complaints in response to applications under the RTI Act, as per a media report of April 2021 citing official records, backlog of only second appeals was more than 30,000. More than half of them were filed between 2015 and 2019, and they were yet to be disposed. Despite the huge backlog, three posts are lying vacant in the commission.

Odisha: The Odisha SIC is functioning with five commissioners despite having a large pendency of nearly 17,500 appeals and complaints.

Rajasthan: The Rajasthan SIC is functioning with five commissioners despite a backlog of nearly 18,000 appeals and complaints.

West Bengal: The West Bengal SIC is functioning with two commissioners for the last several months, despite a backlog of more than 9,000 appeals and complaints.

2. Number of Appeals & Complaints Dealt with by ICs

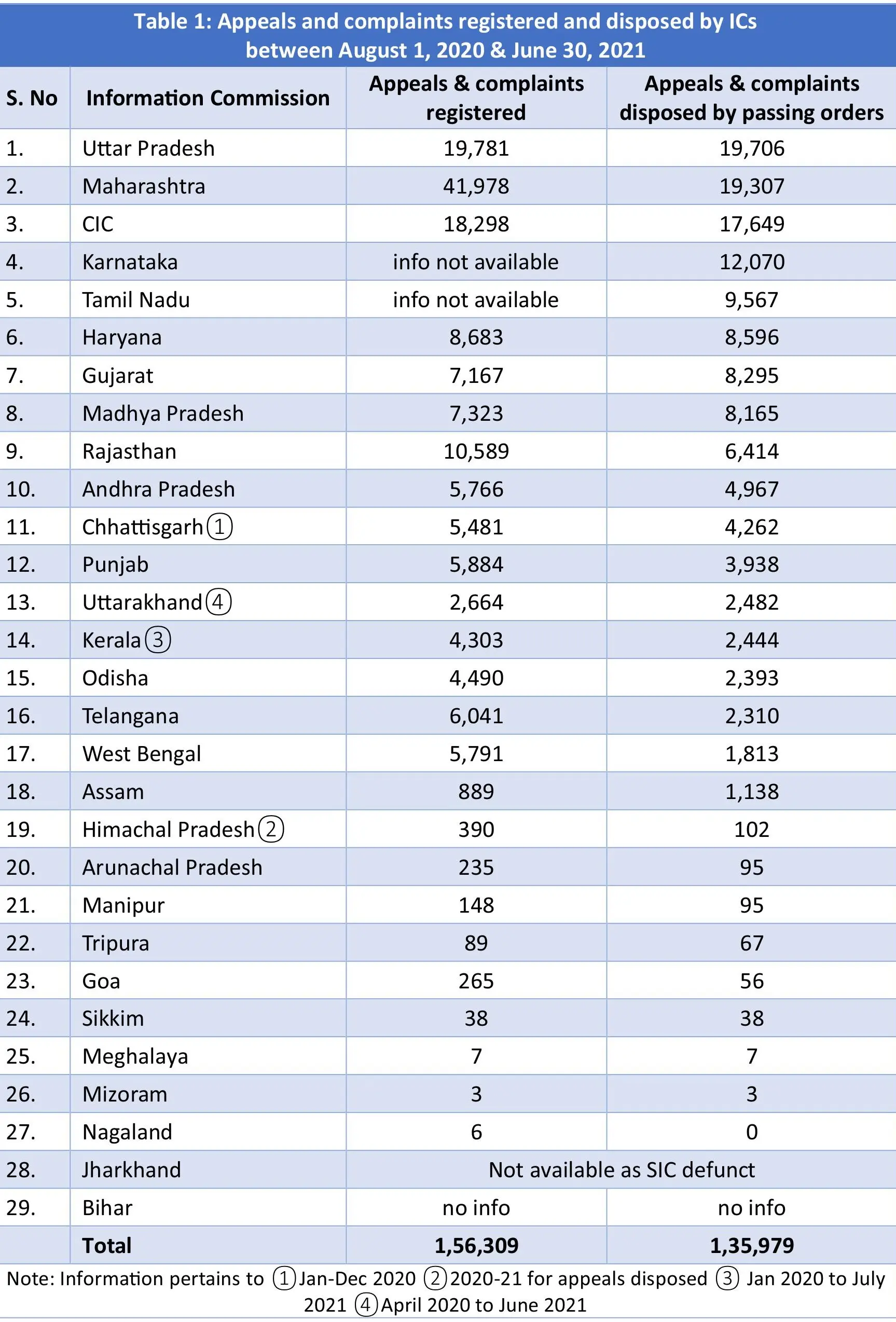

It is to be noted that 1,56,309 appeals and complaints were registered between August 1, 2020 and June 30, 2021 by 25 information commissions for whom relevant information was available. During the same time period, 1,35,979 cases were disposed by 27 commissions for whom information could be obtained.

The commission-wise break up of appeals and complaints registered and disposed is given in Table 1:

3. Backlogs in Information Commissions

3.1 Pending Appeals and Complaints

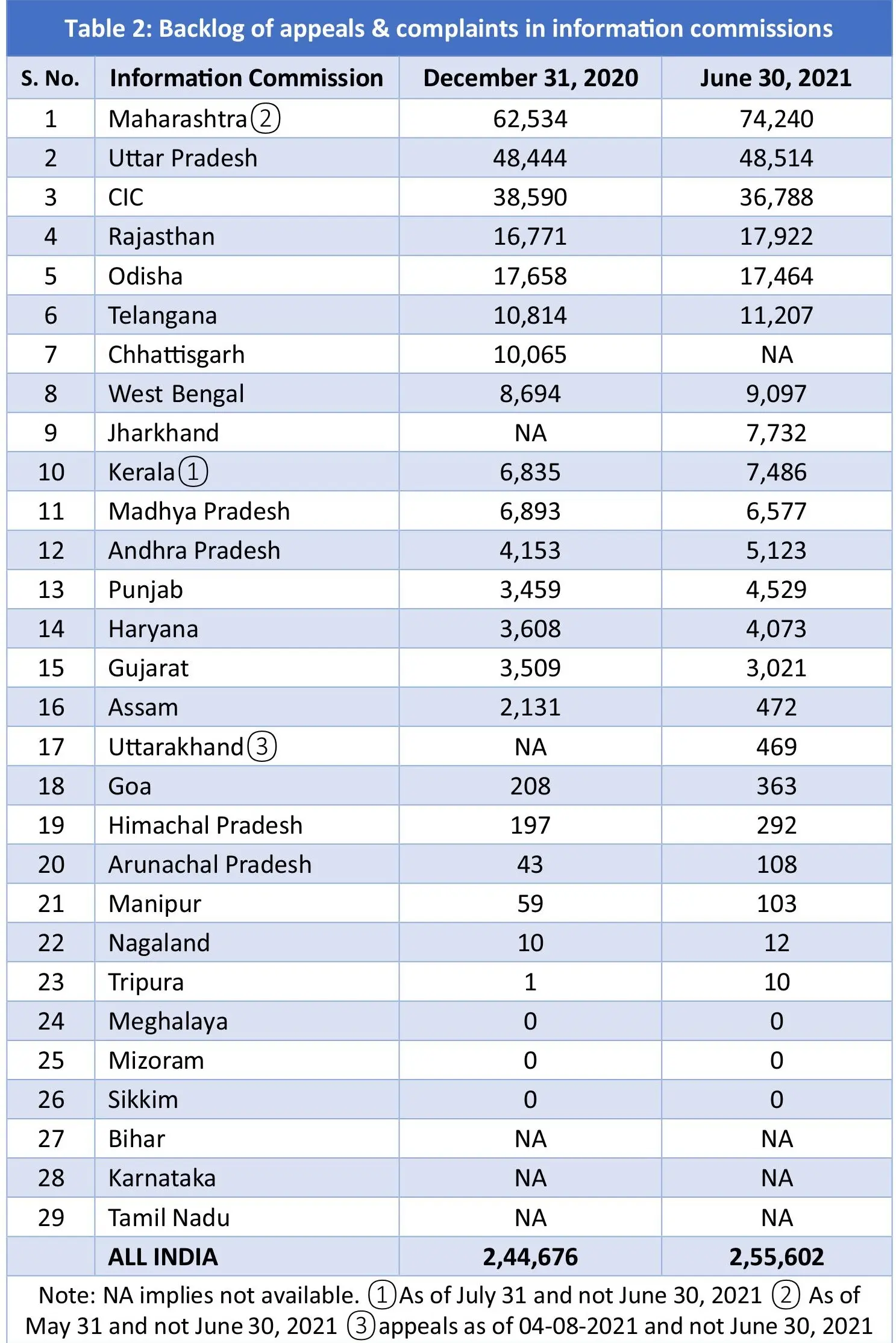

The number of appeals and complaints pending on June 30, 2021, in the 26 information commissions, from which data was obtained, stood at 2,55,602.

The backlog of appeals/complaints is steadily increasing in commissions. The 2019 assessment had found that as of March 31, 2019, a total of 2,18,347 appeals/complaints were pending in the 26 information commissions from which data was obtained. The commission-wise break-up of the backlog of appeals and

complaints is given in Table 2.

3.2 Estimated Time Required for Disposal of an Appeal/Complaint

Using data on the backlog of cases in ICs and their monthly rate of disposal, the time it would take for an appeal/complaint filed with an IC on July 1, 2021 to be disposed was computed (assuming appeals and complaints are disposed in a chronological order). The analysis presented in Table 3 shows that the Odisha SIC would take six years and eight months to dispose a matter. A matter filed on July 1, 2021 would be disposed in the year 2028 at the current monthly rate of disposal! In Goa SIC, it would take five years and 11 months, in Kerala four years and 10 months and in West Bengal 4 years and 7 months.

The report shows that 13 commissions would take one year or more to dispose a matter, which is considerably higher than the figure from the 2020 report wherein it was found that nine commissions would take more than a year.

4. Penalties Imposed by Information Commissions

The RTI Act empowers the ICs to impose penalties of up to Rs. 25,000 on erring PIOs for violations of the RTI Act. The penalty clause is one of the key provisions in terms of giving the law its teeth and acting as a deterrent for PIOs against violating the law.

Whenever an appeal or a complaint provides evidence that one or more of the violations listed in the RTI Act has occurred, the commission should initiate penalty proceedings under Section 20.

The report found that ICs imposed penalty in an extremely small fraction of the cases in which penalty was imposable. In fact, commissions appear to be reluctant to even ask the PIOs to give their justification for not complying with the law.

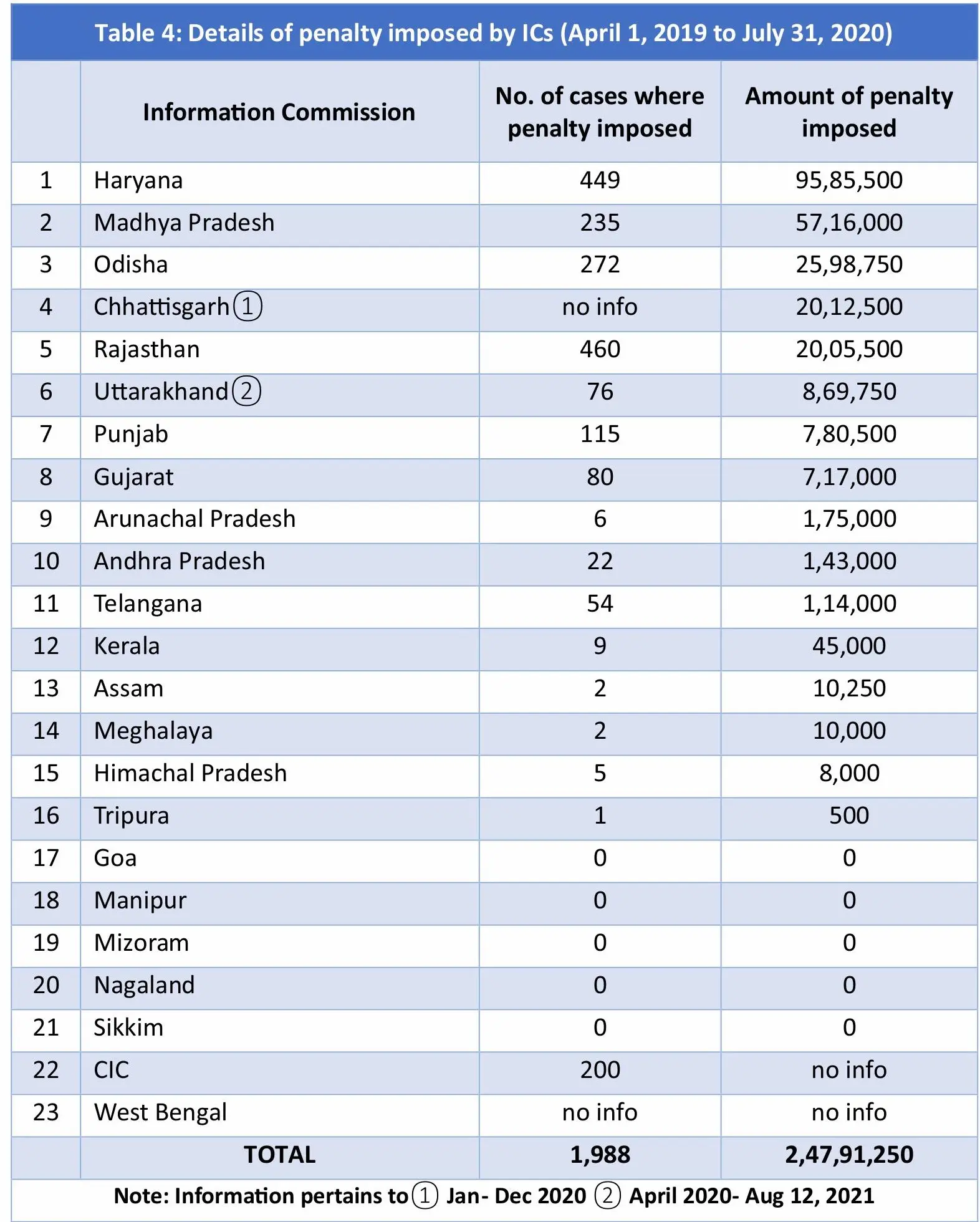

In terms of penalty imposition, of the 21 commissions which provided relevant information, penalty was imposed in a total of 1,988 cases. Penalty amounting to Rs. 2.48 crore was imposed by the 21 commissions during the period under review.

The commission-wise details are provided in Table 4.

In terms of the quantum of penalty imposed, Haryana was the leader (Rs. 95.86 lakh), followed by Madhya Pradesh (Rs. 57.16 lakh), and Odisha (Rs. 25.98 lakh).

5. Transparency in the Functioning of Information Commissions

Much of the information sought as part of this assessment should have been available in the annual reports of each commission. Section 25 of the RTI Act obligates each commission to prepare a “report on the implementation of the provisions of this Act” every year which is to be laid before Parliament or the state legislature. However, the performance of many ICs, in terms of publishing annual reports and putting them in the public domain, was found to be dismal. For instance, 21 out of 29 ICs (72%) have not published their annual report for 2019-20. Only the CIC and SICs of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Mizoram, Nagaland and Uttar Pradesh have published their annual report for 2020 and made them available on their official websites.

In terms of availability of annual reports on the website of respective ICs, 7% of ICs have not made their latest annual report available on their website.

NEXT »