Winning at All Costs

A Mirage called Electoral Reforms!

Swapna Jha

An analysis by the National Election Watch and Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR) of the self-sworn affidavits of candidates who contested in the recent assembly elections of Goa, Manipur, Punjab, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh threw up alarming, but predictable findings.

Out of 6874 candidates analysed, 1694 (25%) have declared criminal cases against themselves in their affidavits. In a frightening turn of events, 1262 (18 %) candidates have declared serious criminal cases against themselves. Also, 44 candidates have declared cases related to murder (IPC Section-302) against themselves.1

Candidates did not fare better when it came to gender crimes. As high as 107 candidates have declared cases related to crime against women. Out of 107 candidates 16 candidates have declared cases related to rape (IPC Section-376, 376D & 376(2) (n)).2

Political parties who distribute tickets to candidates have done their bit to strengthen the nexus between crime and politics. This is not surprising, given that there is no incentive for them to find cleaner candidates who find it tough to win without using excessive money or muscle power. It seems obvious, therefore, that absence of electoral reforms is serving the interest of those who try every trick to manipulate the popular will.

Common Cause has been proactively trying to remedy this, by working for a more transparent and robust electoral system. Our founder-director Mr H.D. Shourie wrote as far back as in 1999: “There is now a definite nexus between political parties and anti-social elements. This unfortunate position has arisen despite (or because of) the provision in Representation of People Act (1951) that a person ‘convicted’ under any of the offences mentioned in its Section 8 is debarred from standing for election for a period of six years from the date of conviction.”

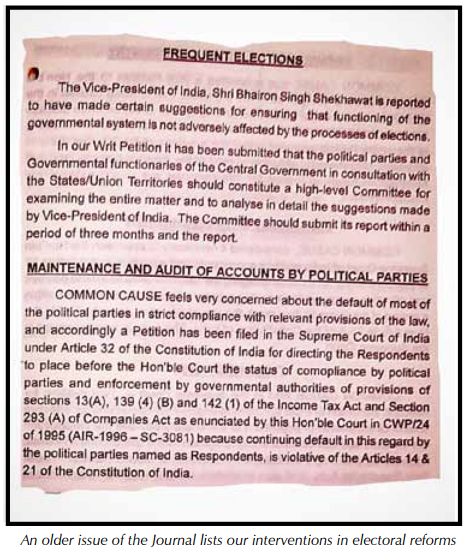

Common Cause has been leading from the front, through representations, PILs, and other democratic interventions, some of which are mentioned below.

Interventions for a Cleaner Polity

In 1994, Common Cause approached the Supreme Court to bring transparency to the election expenses

of the candidates contesting elections. The petition contended that the political parties had done precious nothing even though they were required to maintain audited accounts and comply with the other conditions under Section 13A of the Income-tax Act to be eligible for tax exemption. After all, the citizens, in a democracy, have a right to know the source of expenditure incurred by political parties and contesting candidates.

In a landmark judgment on our PIL, the Supreme Court held that the political parties were under a statutory obligation to file regular IT returns and that failure to do so rendered them liable for penal action. This judgment not only marked a significant progress in the campaign for a cleaner polity, but also paved the way for mandatory declaration of assets by the candidates.

Crime and Politics Nexus

Even though the judgement was a watershed moment for India’s autocratic parties, we decided to continue the crusade. In 2011, Common Cause, along with other civil society partners, filed a PIL in the Apex Court for decriminalising politics. This PIL sought expeditious disposal of criminal cases against Members of Parliament and Legislative Assemblies. It also challenged the powers of Section 8(4) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (RPA), whereby the disqualification of candidates following their conviction was automatically suspended on filing an appeal or a revision application.

In the course of the hearing, the Court requested the Law Commission to submit its report on specific issues highlighted by it. The Commission submitted its recommendations in the form of its 244th report called Electoral Disqualifications. Subsequently, on March 10, 2014, the Supreme Court in its interim order held that trials in criminal cases against lawmakers must be concluded within a year of the charges being framed. The Court also directed that trials must be conducted on a day-to-day basis. It said that if a lower court is unable to complete the trial within a year, it will have to submit an explanation to the Chief Justice of the High Court concerned and seek an extension of the trial.

Unfortunately, even after a lapse of more than eight years, the order of the Apex Court is yet to be implemented. The prayer of Common Cause to hold Section 8(4) of the RPA as unconstitutional was granted in a separate PIL. The Apex Court held that the Parliament did not have the competence to provide different grounds for disqualification of applicants for membership and sitting members.

Powers of Election Commission

Common Cause has intervened whenever the power of the constitutional authorities tasked with ensuring free and fair election has been challenged or sought to be diluted. In 2011, former CM of Maharashtra Ashok Chavan challenged the power of the Election Commission (EC) to issue notice under Section 10 A of the RPA, seeking to disqualify a candidate on account of incorrect return of election expenses, in the Delhi High Court. The High Court upheld the EC’s power to inquire into the correctness of the account of election expenses filed by a candidate. Subsequently, Mr. Chavan filed a Special Leave Petition (SLP) against this order.

The Union government then told the Supreme Court in a counter affidavit, that according to it, the EC had no power to disqualify a candidate, based on reasons like “correctness or otherwise” of his/her election accounts. It claimed that in terms of Section 10A of the RPA and Rule 89 of the Conduct of Election Rules, the power of the Commission to disqualify a person arose only in the event of failure to lodge an account of election expenses and not for any other reasons.

It was ironic that having set up so many Commissions in the past to suggest cures for an ailing democracy, the same executive saw no wrong in the incorrect filing of election expenditure. Not only was it seeking to undo the EC’s acclaim of conducting elections with integrity but was also trying to reverse the law already settled by the SC in the past. Reporting on the incident, noted journalist and Magsaysay Award winner P. Sainath underlined the ridiculousness of the government’s argument in his article for The Hindu: The government’s position implies, an outraged Election Commission source told The Hindu, “that a candidate can fill in zeros in every column and submit his accounts without fear. As long as he lodges them and does so on time.”

Common Cause made up its mind to put its weight behind the EC in this matter. Hence, it made an application to intervene in the SLP in 2011, along with other like-minded civil society partners and eminent citizens. Dismissing Mr. Chavan’s SLP, the Supreme Court, in its judgement of May 5, 2014, upheld the EC’s disqualification of Mr Chavan, for three years. This judgment is a milestone in establishing the right of the EC to take steps to ensure free and fair elections.

Challenging the Electoral Bonds

Very soon, another instrument, which seriously undermines the accountability of the political class, was announced in the form of Electoral Bonds in the 2017 Union Budget. Common Cause and the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) challenged these bonds, which were introduced by amending the Finance Act 2017. These bonds have not only made electoral funding of political parties more opaque, but has also legitimised high-level corruption at an unprecedented scale by removing funding limits for big corporates and opening the route of electoral funding for foreign lobbyists. The PIL sought direction from the Supreme Court to strike down the amendments brought in illegally as a “Money Bill” in order to bypass the Rajya Sabha.

Ahead of the Assembly elections in four states and a Union Territory (UT), an application was filed again in the Supreme Court on March 6, 2021. This was to stop the sale of electoral bonds till their validity, already under examination by the Apex Court, was finally decided.

On March 26, 2021, the SC dismissed the application, saying that it did not find any justification to stay fresh sales of electoral bonds ahead of the state Assembly elections.

The Bench, headed by Chief Justice S.A. Bobde, declined to stay their sale, noting that the bonds were allowed to be released in 2018 and 2019 without interruption and that “sufficient safeguards are there.” The EC, which had red flagged the issue in 2017 and 2019, took a different stand while claiming that staying electoral bonds would mean going back to the era of unaccounted cash transfers.

Use of Inaccurate Data by ECI

Subsequently, Common Cause, along with ADR, filed another writ petition in 2019, challenging electoral irregularities and to ensure free and fair elections and the rule of law. The PIL was filed under Article 32 of the Constitution to ensure that the democratic process is not subverted by electoral irregularities and for the enforcement of fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution. The instant writ petition highlighted the dereliction of duty on the part of the ECI in declaring election results (of the Lok Sabha and State Legislative Assemblies) through Electronic Voting Machines, based on accurate and indisputable data which is put in the public domain.

The petitioners sought a direction for the ECI not to announce any provisional and estimated election results prior to actual and accurate reconciliation of data. They further sought a direction to the ECI to evolve an efficient, transparent, rational and robust procedure/ mechanism by creating a separate department/ grievance cell. The cell is to be used for investigation of discrepancies in election data and for responding to the elector’s queries on the same. A notice was issued, returnable on February 17, 2020.

On February 24, 2020, the Bench of the Chief Justice and Justices B.R. Gavai and Surya Kant directed this matter to be listed on a non-miscellaneous day after four weeks. Meanwhile, the counter-affidavit is yet to be filed.

Political Ads at Taxpayer’s Expense

In its bid to ensure that the govt in power did not waste public funds on large scale advertisements, Common Cause approached the Apex Court way back in 2003. Despite the Supreme Court judgment in 2015, issuing several guidelines aimed at regulating govt advertisements to check the misuse of public funds, the trend continues unabated.

According to an analysis of the annual audit reports of political parties submitted to the ECI, between 2015 and 2020, more than Rs 6,500 crore was spent on elections by 18 political parties, including seven national parties and 11 regional parties. Of this, political parties spent more than Rs 3,400 crore, or 52.3 per cent, on publicity alone.3 Therefore, Common Cause has once again approached the Supreme Court in 2022, seeking directions to put a curb on wastage of public money by political parties to gain mileage through laudatory and self-congratulatory advertisements.

In the background of the current election extravaganza, it has filed the PIL seeking appropriate directions to restrain central and state governments from using public funds on govt advertisements in ways that are completely malafide and arbitrary and amount to breach of trust as well as abuse of office. They should also not be in violation of the directions/ guidelines issued by the Apex court and the fundamental rights of citizens under Article 14 and 21 of the Constitution.

Conclusion

Introduction of the ‘Electoral Bonds’ and ‘Election Laws Amendment Act 2021’ are structural changes which are bound to fundamentally alter the parliamentary election framework. While the govt claims that the Electoral Bond Scheme is, “an unprecedented step towards cleansing the process of funding of political parties” believers in transparency and accountability are not convinced. Academician Milan Vaishnav writes that “in truth, electoral bonds have only legitimized opacity. The government has promised reform, while doubling down on nefarious old habits. But as a recent five–part investigative series in HuffPost India—#PaisaPolitics—authored by the journalist Nitin Sethi reveals, this new instrument has done something more: it has intensified the crisis confronting India’s much-vaunted apex institutions.”4

Similarly, linking Aadhaar to electoral rolls has been mired in debates. On the face of it, the govt sees this move as a means to purify the electoral rolls. Supporters also argue that this legislation will allow for remote voting, helping migrant voters. But many opposition leaders feel that this legislation could lead to the disenfranchisement and vicious profiling of the legitimate voter.

With ‘winning at all costs’ becoming the mantra of all political parties, electoral reforms that will fundamentally lead to free and fair elections seem a pipedream. As Mr. Shourie put it succinctly: “The election system is the bedrock of our democracy; however, there are some basic flaws in it which are detrimental to the interest of democracy. The Election Commission has repeatedly brought these flaws to the notice of the government but has not been able to get remedial action taken.”

Endnotes

- Analysis of Criminal Background, Financial, Education, Gender and other Details of Candidates (2022, March 4). Association for Democratic Reforms. Retrieved on March 9, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3uJHjFp

- Id.

- Indiaspend staff (2021, December 26) Big Spenders: Election expenses cross Rs 6500 crore shows data, Business Standard. Retrieved on March 7, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3tBqZa7

- Vaishnav, Milan (2019, November 25) Electoral Bonds: The Safeguards of Indian Democracy are crumbling, HuffPost India. Retrieved on March 9, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3JECJhO

NEXT »