Declining Judicial Capacities

Chronic Delays, Pendencies, and Vacancies

The Capacity Deficits

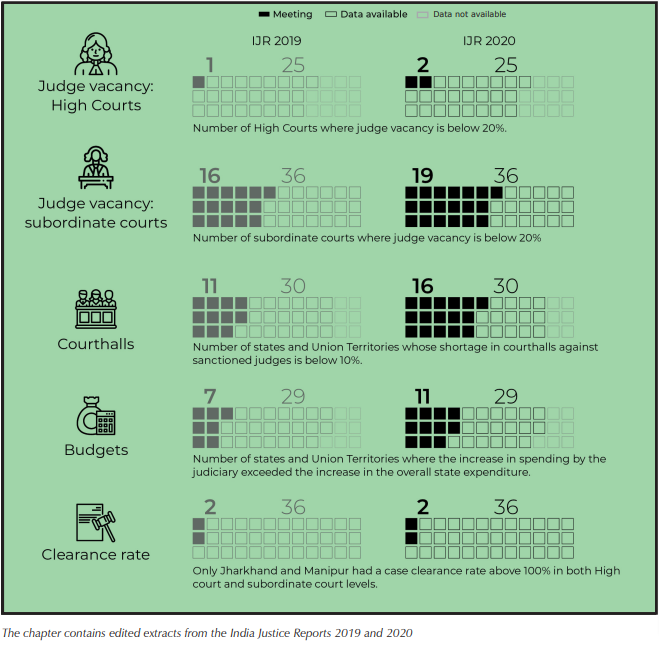

The state of the judiciary in India has been a cause of concern not just among the policy-makers and the legal community, but also in the larger public sphere. Judicial delays, huge pendencies and the dearth of human resources and infrastructure are issues that have been highlighted time and again. IJR 2020 reports that only two states have High Courts with judge vacancies of less than 20 percent, while the vacancies in all other states and UTs is much higher than 20 percent. Only Jharkhand and Manipur had a case clearance rate above 100 percent in both High Court and subordinate court levels. About one in four cases in the subordinate courts of India has been pending for more than five years.

In the IJR series, the purpose is to study the capacity of the criminal justice system to be able to deliver justice. To make this assessment, we look at each pillar through these thematic lenses: human resources, infrastructure, diversity, workload and budgets. The reports also analyse the progress made by the states in some of these indicators over the years, particularly those which have clear benchmarks set out by the states themselves. The states are then ranked against these benchmarks in comparison to one another to track the relative capacity of each pillar in the state to be able to perform its functions effectively.

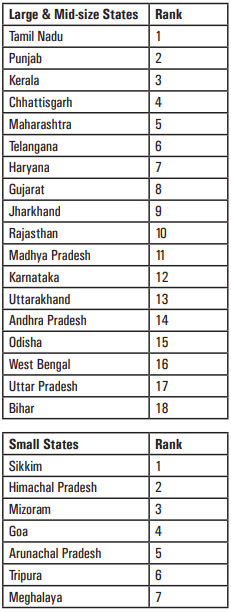

A total of 23 indicators were analysed to study the capacity of the judiciary across states. The analysis showed that as of 2020, among the large and mid-sized states, Tamil Nadu had the highest rank, while Bihar ranked the lowest. Amongst the 25 small, mid-sized and large states that were ranked, nine showed overall improvement in judicial capacity since 2019, while 10 states showed a downward trend.

Tamil Nadu and Punjab retained their first and second ranks respectively since 2019, while UP and Bihar were the worst ranking states in both years under the judicial pillar. Telangana jumped five spots to the 6th position; Jharkhand from 14th to 9th; Karnataka from 16th to 12th. Various factors contributed to improvements including better case clearance rates in subordinate courts and a reduction in the number of cases pending over 10 years. The most pronounced falls were seen in Haryana (third to seventh); Odisha (ninth to fifteenth), Madhya Pradesh (sixth to eleventh), and West Bengal (tenth to sixteenth). This is mainly due to the large number of vacancies that persist in their high courts.

In this chapter, we look at some of the key findings of IJR 2020 under the judiciary pillar.

Human Resources

Nationally, average cases pending in High Courts rose from about 40.12 lakhs in 2016-17 to 44.25 lakhs in 2018-19, and in lower courts from 2.83 crores to 2.97 crores. Though the number of pending cases rose, except for Chandigarh’s lower courts, no single High Court or state’s lower judiciary had a full complement of judges in place. Over a five-year period, only four states have reduced vacancies at both levels. On average, one in three judges in the High Court was missing and one in four among subordinate judges. In fact, in the two years between 2016-17 and 2018-19, vacancy levels increased in 10 High Courts and 15 subordinate courts. In High Courts, the range varies from 70 percent (Andhra Pradesh) to eight percent (Sikkim). In 16 out of 18 large and mid-sized states, vacancies run at over 25 percent.

There were some sharp contrasts as well. Even as Karnataka nearly halved its subordinate court vacancies, in Tamil Nadu (10 percent to 22 percent) and Uttar Pradesh (31 percent to 39 percent) vacancies increased significantly, while Meghalaya’s went up from 42 percent to 60 percent.

Shortage of non-judicial staff also hampers the functioning of the judiciary. Available data (2018- 19) from High Courts signposts that eight of the 18 large and mid-sized states—Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan, Odisha, Uttarakhand, Bihar—work with more than 25 per cent nonjudicial staff vacancies.

Diversity

Despite a wide acceptance of the value of diversity for improved delivery of justice, the data on religious and social diversity amongst judges remains unavailable, particularly in the subordinate judiciary. Gender diversity is zmore trackable.

On average, the share of women judges in the High Courts increased marginally from 11 percent to 13 percent, while in subordinate courts it increased from 28 percent to 30 percent Nevertheless, over a two-year period, twelve High Courts and twenty-seven subordinate courts improved their share of women judges. This means that while one in three judges in the subordinate courts is a woman, in the High Courts, only one in nine judges is a woman. The glass ceiling remains intact. Illustratively, at 72 percent, Goa had the largest share of women in their subordinate courts. This drops to 13 per cent in the High Court.

The biggest improvements in gender diversity in High Courts took place in Jammu and Kashmir (15 percentage points), Chhattisgarh (14 percentage points), and Himachal Pradesh (11 percentage points). Previously, none of the three states had a women judge. The largest fall of 6.3 percentage points was in Bihar, which, as of August 2020, has no woman High Court judge. Since 2018, the high courts of Manipur, Meghalaya, Tripura and Uttarakhand also continue to have no women judges.

Budget

The report uses per capita expenditure as a comparator between states to evaluate the adequacy of budgetary allocations to the judiciary. The average five-year change in expenditure, when measured against the change in the total state expenditure, is indicative of the proportion of their incremental budgets that states were able/ willing to allocate. This can be interpreted as being reflective of the priority that a state accords to its judiciary. In the large and mid-sized category, Haryana spends the most (?230) per capita, while West Bengal at the bottom spends one-fourth of that (?58). In the small state category, the per-capita spend ranges from ?496 in Sikkim to one-fourth of that (?119) in Arunachal Pradesh.

Pendency

Between 2016–17 and 2018–19, the average number of pending cases in High Courts has increased by 10.3 percent and in subordinate courts by five percent.

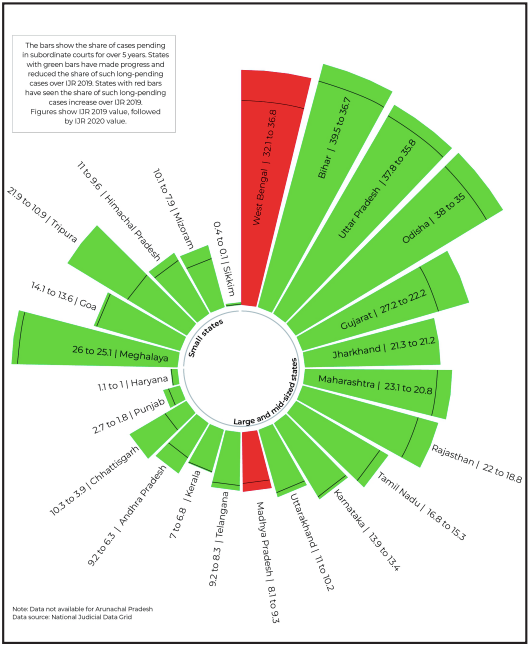

In 21 of the 24 ranked states, cases pending in subordinate courts for above five years have decreased in the last two years. However, in eight states, such cases still amount to over 20 percent of pending cases. In West Bengal, for instance, the share of cases pending over five years has increased by nearly 5 percent to about 36.8 percent.

Vacancy

In 2016–17, average High Court judge vacancies were at 42 percent, subordinate courts at 23 percent and only four states and two UTs had sufficient courtrooms. Nationally, as of 2018-19, vacancies have come down to 38 percent in the High Courts and 22 percent in the subordinate courts. The number of court halls has moderately improved, though they remain much fewer than required. On the whole, state expenditure on the judiciary has increased by 0.02 percent.

Infrastructure

Logic demands that for every judge there must be a physical courtroom. The shortage of court halls has stayed at around the same levels at 14 percent. Between 2018 and 2020, the number of functional court halls has increased from 18,444 to 19,632.

However, if the full complement of sanctioned judge strength were appointed, there would be a shortfall of 3,343 court halls. The larger states made better headway in constructing more courts but in states such as Arunachal Pradesh (0 percent to 21 percent), Madhya Pradesh (13 percent to 23 percent), and Uttar Pradesh (14 percent to 29 per cent), shortages have increased since the previous report.

Workload

Vacancies and poor infrastructure impact judge workloads. Looked at across five years, the total number of pending cases in 12 High Courts and subordinate courts in seven states/UTs has declined. Between 2018 and 2020, the subordinate courts of 28 states/ UTs also managed to reduce the share of cases pending for more than five years. Among large and medium states, only West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh bucked this trend. In these two states, pending cases in subordinate courts increased by over 14 percent and those over five years in court by 37 percent. At the national level, cases across subordinate courts are pending for three years on average. In eight states, one in five cases still remains pending for more than five years.

Nationally, the average case clearance rate is higher in subordinate courts (93 percent) than in High Courts (88.5 percent). At the subordinate courts level, 12 states/UTs had a case clearance rate of more than a 100 percent, compared with only four High Courts. On a five-year basis, the picture is marginally better: only 11 states/ UTs’ High Courts and the subordinate courts of 17 states/UTs have managed to improve their case clearance rates.

Overall Ranking - Judiciary

Below the five top states there were several shifts in ranking: Telangana jumped five spots to sixth position; Jharkhand from fourteenth to ninth; Karnataka from sixteenth to twelfth. Uttar Pradesh and Bihar have, however, remained at the bottom of the table. A combination of frailties particularly at the

subordinate court level keep them at the bottom of the table including vacancies amongst judges, cases pending for over five years, and the average number of years a case remains pending. Among smaller states, Sikkim retained its first position while Meghalaya dropped three spots. The drop can be attributed to increasing vacancies at both court levels, lack of women judges at the High Court, and a growing deficit of court halls.

NEXT »