Measuring Police Adequacy

Key Findings from the India Justice Report

The Capacity Deficits

Police is perhaps one of the most people-facing pillars of the Indian justice system, acting as the first point of interface between the public and other pillars such as the judiciary and prisons. Even as there is overlap between all the pillars, the work of the police is one of the essential contributors to the level of functioning of other pillars as well.

In the IJR series, the purpose is to study the capacity of the criminal justice system to be able to deliver justice. To make this assessment, we look at each pillar through these thematic lenses: human resources, infrastructure, diversity, workload, budgets and five-year trends. The reports also analyse the progress made by the states in some of these indicators over the years, particularly those which have clear benchmarks as set out by the states themselves. The states are then ranked against these benchmarks in comparison to one another to track the relative capacity of each pillar in the state to be able to perform its functions effectively.

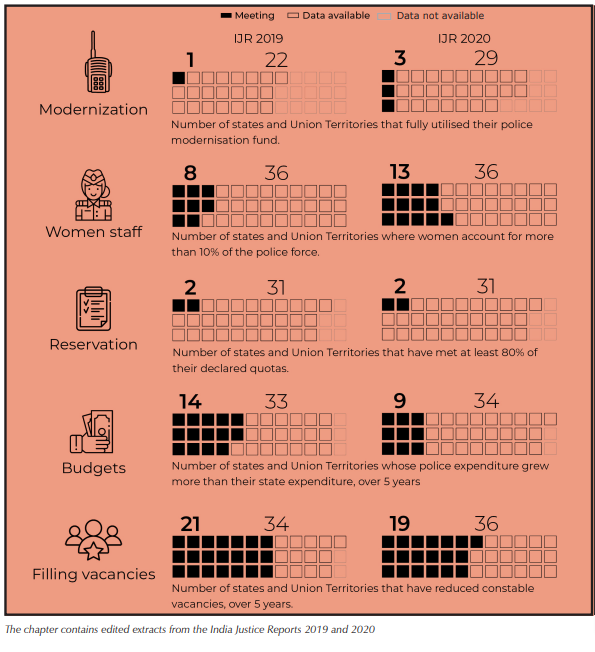

A total of 26 indicators were analysed to study the capacity of police forces across states. The IJR 2020 also looked at the status of state police citizen portals and mapped the accessibility of facilities available in these portals.

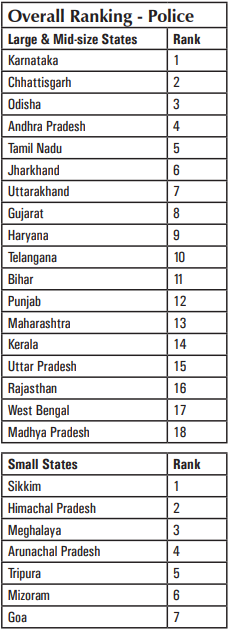

As of 2020, among the large and mid-sized states, Karnataka had the highest rank, while Madhya Pradesh ranked the lowest. Amongst the 25 small, mid-sized and large states that were ranked, 13 showed overall improvement in ranking since 2019, while 11 states showed a downward trend. The starkest amongst the latter were Punjab and Maharashtra, which respectively dropped from the third and fourth rank in 2019 to the 12th and 13th rank in 2020, primarily due to poor utilisation of the Modernisation Fund, and fiveyear trends in which officer and constable vacancies increased.

In this chapter, we look at some of the key findings of IJR 2020 under the police pillar.

Diversity

Reservations for women vary from 10 to 38 percent. Following the 2009 Government of India advisory, nearly all UTs and nine states adopted a target of 33 percent reservation for women. Ten states set their quota at 10 or less than 10 percent and eight have no reservations. Tamil Nadu is the only state to have reduced its target from 33 to 30 percent since 2017. Bihar stands out with the highest target at 38 percent.

In terms of actual numbers, though, the national average for women remains a lowly 10 percent. This is a marginal increase from the 7 percent seen in 2017.

In 2017, no state had been able to fill its reservation quotas at officer levels, let alone exceed them. However, in 2020, only Karnataka has been able to fill, and exceed its SC, ST and OBC quotas by 26, 86 and 64 percent respectively. Six states/ UTs meet or exceeded their SC quota while seven states/UTs met or exceed their ST officer quota. Eight states reached or exceeded their OBC officer quota. None of the UTs were able to meet their quotas.

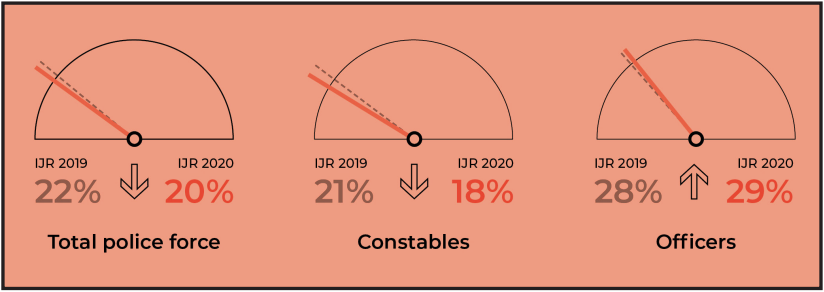

It remains a concern that nationally, about one in three officers —tasked with investigation, supervision and planning—are missing from the police. In more than half of all states/UTs, the vacancies amongst officers have in fact increased significantly, with Madhya Pradesh (19 percent to 49 percent), Jammu and Kashmir (14 percent to 34 percent) and Arunachal Pradesh (18 percent to 33 percent), showing the largest jumps over three years. Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, with one out of every two officer posts unfilled, have the most vacancies. At the other end of the spectrum, Sikkim has 22 percent more officers than its sanctioned strength. Eleven states/UTs are functioning with an officer vacancy of 30 percent or more. In other words, in 11 states/ UTs, the police force is working with less than two-thirds of its sanctioned staff. Only seven states/UTs work with vacancies below 10 percent.

Over the five years between 2015–19, 17 states/UTs show a trend of increasing vacancy at the level of supervisory staff. Five out of seven small states similarly display a steadily increasing trend in vacancies

As of 2020, approximately one out of every five constable posts remains vacant nationally. Telangana and West Bengal have the highest vacancy at 40 percent each. The states with the least vacancy include Uttarakhand (3 percent), Himachal Pradesh (5 percent) and Goa (4 percent). Nagaland has hired 15 percent above its sanctioned numbers. Only in 11 states/ UTs are constabulary vacancies less than 10 percent.

This report notes a steady effort by states/UTs to reduce shortfalls at the constabulary level. Over a fiveyear period (2015–2019), shortfalls at this level reduced in as many as nineteen states/UTs.

Training

Training accounts for a mere 1.13 percent of the total national spend on policing or roughly ?8,000 per police person. This varies a great deal from state to state. Mizoram, with a force of over 5,406, spends the highest at about ?32,310 per head. This is followed by Delhi (?24,809) and Bihar (?15,745). According to BPR&D data, Kerala, with nearly 53,000 personnel, spends nothing while Tamil Nadu spends ?2. Among the small states, Himachal Pradesh spends the least (?511).

Number of Training Institutes

Given its importance to capacity building, IJR 2020 adds police personnel per training institute as an indicator to measure the adequacy of training institutes. Without exploring the content, duration, and quality of training, the data indicates that large numbers must be put through training —induction, inservice as well as other specialised trainings—in few facilities. Illustratively, on average, each of the 11 training institutes in Uttar Pradesh has an average workload burden to train over 37,700 personnel while Manipur’s sole training institute is intended to handle about 35,000 trainees. In comparison, Tamil Nadu’s 23 institutes are to train an average of about 5,400 personnel each. Among small states, the range varies from 3,244 personnel (Sikkim) to 18,849 personnel (Himachal Pradesh) annually

The effect of the crunch in training facilities is felt most acutely in ensuring in-service training. For example, over five years (2012–16) on average, only 6.4 percent of the police have received in-service training. That means that over 90 percent personnel, including those who deal with the public on a dayto-day basis, do not receive regular up-to-date specialised training after the first induction course.

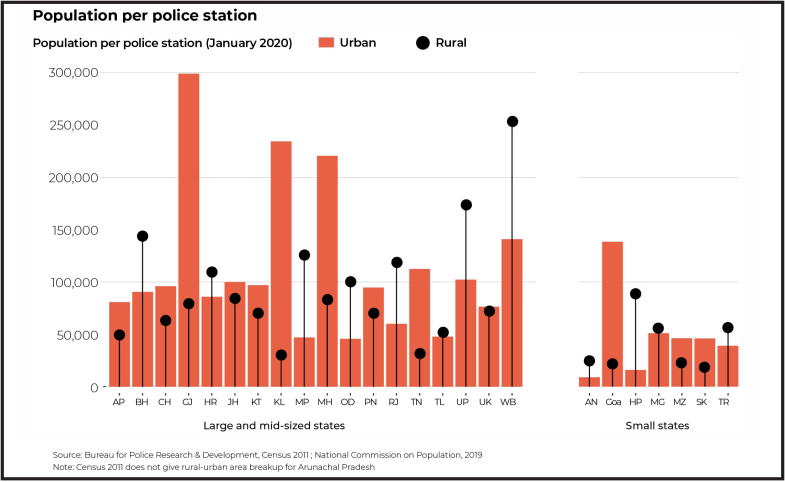

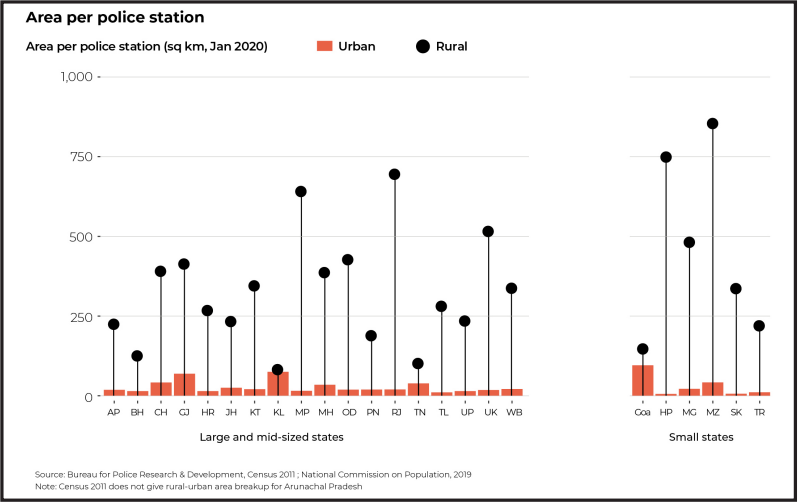

The Rural-Urban Divide

In several states, the average population per police station is lower in rural locations than in urban locations. However, in nearly all states, rural police stations cover a significantly higher average area than urban police stations, the exception being Kerala.

Modernisation Fund

The Ministry of Home Affair’s Modernisation Scheme assists state forces to meet capital expenditure, such as the construction of new buildings and acquisition of technology and equipment. Data for utilisation in 2019–2028 shows an overall decline in the average utilisation compared to 2017—falling from 75 percent to 41 percent.

West Bengal, Mizoram and Nagaland were the only states which were able to utilise 100 percent of the fund. Odisha (10 percent) and Tripura (2 percent) could utilise 10 percent or less while Manipur, Meghalaya, Punjab, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh did not use any.

Evaluating Technology

Technology has been recognised as an integral component of efficient policing. Whether the use of technology has indeed improved people’s access to, and experience of, basic policing services requires rigorous assessment. This report makes a beginning by looking at state police citizen portals from user’s point of view—a SMART policing initiative of the Ministry of Home Affairs and an objective under the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network & Systems (CCTNS). IJR 2020 measures compliance by assessing whether states have indeed developed the citizen’s portal; whether they include each of the nine services listed by the MHA; and whether the information provided under each is easy to access. It did not assess whether the information was current, complete or accurate.

The portals were checked thrice from June to October 2020 and were scored on whether each of the nine services was complete in content and whether the portal was available in a state language (other than English).

Despite the push for digitisation, no state offered the complete bouquet of services it is required to; and even with the same service, there are variations in what is provided. Scored for services and language, Punjab and Himachal Pradesh provided 90 percent of expected services. This was followed closely by Chhattisgarh (88 percent), Maharashtra (88 percent) and Andhra Pradesh (86 percent). Six states provided 10 percent or less of these services. Bihar was the only state which did not have a portal, however it did offer some of the nine services on its police website.

Most sites were available in English or Hindi, but not necessarily in the state language. The Delhi portal, for instance, was available only in English while in Jharkhand and Punjab, only certain sections of the site or one of the services were in Hindi or Gurmukhi respectively. For Jammu and Kashmir, there was no ready option to translate the page and for access, the site requested the user to download the Urdu script.

Due to these gaps, the citizen portals in their existing form are falling short of their objective of enabling easy access to select policing services.

NEXT »