Incarceration and Reformation

Data on Prison Capacities

The Capacity Deficits

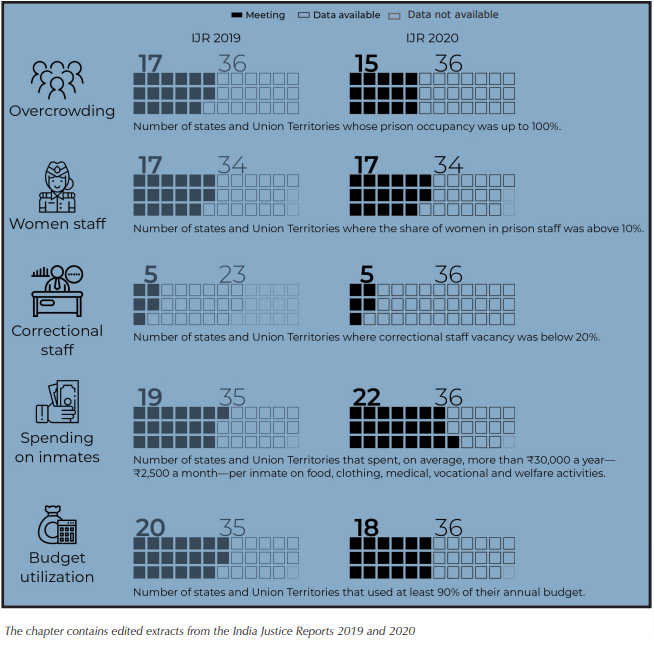

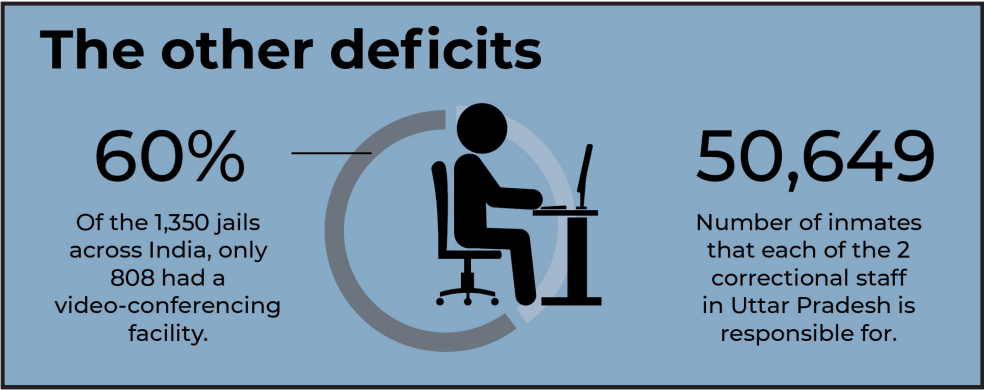

Prison reforms have been on the national agenda since several decades, at least in policy. Several Supreme Court judgements have time and again reinforced the need for addressing chronic issues such as overcrowding in prisons, unnatural deaths in jails, lack of medical facilities, to name a few, directing states to improve prison conditions. However, as the IJR notes, even as of 2020, out of all 36 states and UTs, 21 continue to have prison population of more than a 100 percent, resulting in overcrowding. In half of the states and UTs, women comprise less than 10 percent of the overall staff and correctional staff vacancies continue to be high in a majority of the states and UTs. In UP, for instance, one correctional staff is expected to serve 50,649 inmates.

In the IJR series, the purpose is to study the capacity of the criminal justice system to be able to deliver justice. To make this assessment, we look at each pillar through these thematic lenses: human resources, infrastructure, diversity, workload and budgets. The reports also analyse the progress made by the states in some of these indicators over the years, particularly those which have clear benchmarks set out by the states themselves. The states are then ranked against these benchmarks in comparison to one another to track the relative capacity of each pillar in the state to be able to perform its functions effectively.

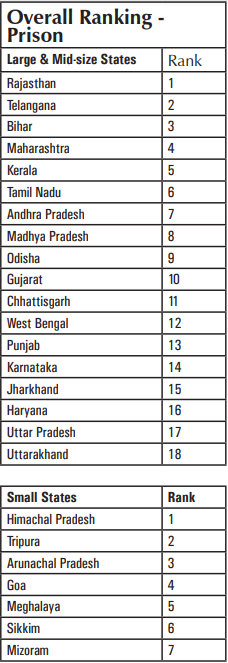

A total of 23 indicators were analysed to study the capacity of prisons across states. The analysis showed that as of 2020, among the large and mid-sized states, Rajasthan had the highest rank, while Uttarakhand ranked the lowest. Amongst the 25 small, mid-sized and large states that were ranked, 10 showed overall improvement in prison capacity since 2019, while 14 states showed a downward trend.

Rajasthan and Telangana showed the most improvement in prison capacities, with the two states going from 12th and 13th rank in 2019 to 1st and 2nd rank respectively in 2020. These shifts were caused by reduced prison occupancy and improvements in the inmate-to-staff ratio. At officer level, half the states/ UTs have about one in three positions vacant. Vacancies range from 75 percent in Uttarakhand to less than one percent in Telangana. Nationally, cadre staff vacancies stand at 29 percent. Amongst states, vacancies range from 64 percent in Jharkhand to none in Nagaland. The national average stands at one probation/ welfare officer per 1,617 prisoners and one psychologist/psychiatrist for every 16,503 prisoners.

In this chapter, we look at some of the key findings of IJR 2020 under the prisons pillar.

Diversity

No state came close to the 33 percent benchmark for gender diversity suggested in policy documents. Women accounted for about 13 percent of staff across all levels —up from 10 percent in December 2016.

Over the last five years (2015– 2019), 28 of 34 states/UTs made slow but steady improvements. Prominent among those that have not are Uttarakhand where the share of women fell to three percent from six percent; and Delhi where women staff fell from 15 down to 13 percent. Uttarakhand with three percent and Goa at two percent have the lowest shares of women working in prisons.

Budget

Nationally, the average spend per prisoner has, however, gone up by nearly 45 percent. Andhra Pradesh, at ?2,00,000 for over 7,500 inmates in 106 prisons records the highest annual spend. Fifteen out of 36 states/ UTs spent less on a prisoner in 2019-20 than in 2016-17. In 2019-20, 17 states/ UTs spent below ?35,000 annually, or less than ?100 a day per person. But the lowest spends per prisoner have gone down further: in 2016-17 Rajasthan at ?14,700 spent the least per inmate but, currently, at ?11,000 Meghalaya spends the least per inmate.

Utilisation of allocated funds fluctuates between beyond 100 percent (Telangana) to as low as 50 percent (Meghalaya). Overall though, over a three-year period, states/ UTs have done worse in terms of utilisation: Gujarat fell from 95 percent to 80 percent; Uttar Pradesh from 94 percent to 83 percent; and Meghalaya from 88 percent to 50 percent. By contrast, Telangana (92 percent to 103 percent), Tripura (75 percent to 99 percent), and Andhra Pradesh (77 percent to 88 percent) are amongst the states to have improved their utilisation.

Video Conferencing

Video conferencing for remand hearings, before a charge sheet is filed was legalised in 2008. Using the latest available figures, IJR 2020 adds this facility as a rankable indicator. Sixteen states/ UTs report that 90 percent of their jails have video-conferencing facilities. Five of the large and mid-sized states though had less than 50 percent; Kerala (42 percent); Rajasthan (38 percent); West Bengal (32 percent); Karnataka (31 percent); and Tamil Nadu (9 %). Despite the newfound significance in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the increasing use of this technology without rigorous oversight monitoring and evaluation of its functioning continues to throw up grave doubts about its impact on the fair trial rights of accused persons. Its routinised use has prompted the Bombay High Court to provide for legal aid lawyers to be present in prison whilst undertrials are produced through video conferencing and also warned that video conferencing facilities cannot be a substitute for producing an accused person before the trial court on scheduled dates.

Infrastructure

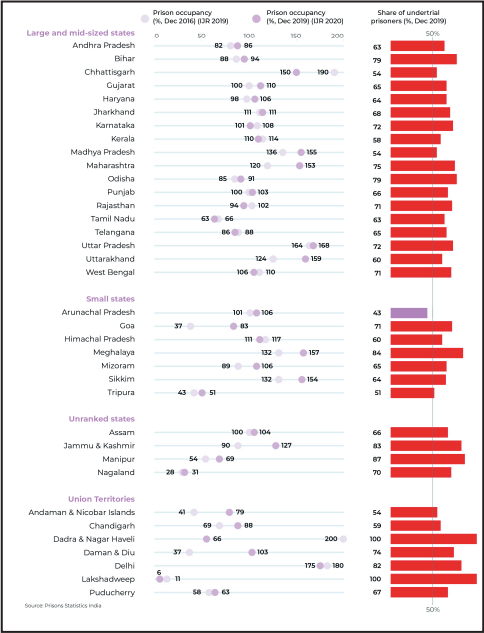

Prison occupancy has increased in 25 states and union territories. Part of the reason is the high proportion of undertrials. In 35 of 36 states/UTs, inmate population has increased by 50 percent.

Infrastructure has not kept pace with the growing inmate population. While the overall prison population has grown to 4,78,600 (PSI 2019) from 4,33,003 (PSI 2016) the number of prisons has come down from 1,412 to 1,350. Several unsustainable sub-jails have been closed down, and their populations must now necessarily be assimilated into the nearest district or central prisons. It is no surprise then that overcrowding is at 19 percent, a jump of five percentage points from 2016 figures. Unnecessary arrests, conservative approaches to granting bail, uncertain access to legal aid, delays at trial, as well as the inefficacy of monitoring mechanisms such as Under Trial Review Committees continue to contribute to overcrowding. The national average disguises the fact that occupancy in 21 states/UTs is over a 100 percent. Twenty states have in fact seen an increase in occupancy in the last two years. The most overcrowded prisons are in Delhi (175 percent), Uttar Pradesh (168 percent), and Uttarakhand (159 percent).

Human Resources & Workload

Prison staff are divided into officers, cadre staff, correctional staff, and medical staff. Nationally, over three years average, vacancy levels across all prison staff remains at a little over 30 percent. Some vacancies may appear to have increased because the sanctioned strength has gone up. For instance, in December 2016, Chandigarh had no vacancies at the officer level. However, now the UT has one out of two officers missing because it increased the sanctioned officer strength from the earlier four to ten.

In order to satisfy the aspiration that prisons must move from being custodial to correctional institutions, prison systems are required to have a special cohort of correctional staff—welfare officers, psychologists, lawyers, counsellors, social workers, among others. The Model Prison Manual, 2016, specifically characterises correctional work as a “specialised field”. However, the years have seen little institutional capacity being built in this area.

The Model Prison Manual, 2016, sets the standard at one correctional officer for every 200 prisoners and one psychologist/ counsellor for every 500. Only Jammu and Kashmir (194), Bihar (167), and Odisha (123) meet this benchmark. While both meet their sanctioned numbers, Uttar Pradesh, despite a prison population of over 100,000, has sanctioned only two correctional officer posts; Jharkhand, with a far lower population of 18,654 inmates, has four.

The Manual also mandates a minimum of one medical officer for every 300 prisoners and one full-time doctor in central prisons. In half the states/UTs about one in four positions remains empty. Nagaland, Lakshadweep, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, and Daman and Diu did not have any medical officers sanctioned while Uttarakhand was once again the only state to have none of their 10 sanctioned posts for medical officers filled. Twelve states/UTs have a shortfall of 50 percent or more medical officers while Punjab and Arunachal Pradesh both have more officers than their sanctioned strength.

As of December 2019, however, no state could provide all its personnel with sufficient training opportunities. Only Telangana provided training to 92 percent of its officers/staff.

Tamil Nadu at 55 percent was a distant second above Maharashtra (43 percent), and Delhi (42 percent). In 28 states, a maximum of one in four could be trained. Among prison training institutes, only three regional training institutes and some state prison training institutes cater to the needs of both officers and cadre staff. The training institutes lack adequate infrastructure and human resources like regular teaching faculty and modern teaching aids to be able to ensure that prison staff undergo refresher trainings on a regular basis.

NEXT »