A battle called crossing the road

We Need Constant Campaigns to Sensitise Drivers

Mohd Aasif *

It’s hard to remember when I had a pleasant walk on the road without the fear of being mowed down by a speeding vehicle. Walking is the most sustainable mode of commute, and yet, a struggle like no other. No journey is complete without crossing the roads, but for non-motorised road users, it has become nothing less than a battle.

A survey by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) shows that 63 per cent of the citizens walk more than 500 metres daily to reach their destinations. Cars and two-wheelers account for 30 per cent of the trips made but occupy 80 per cent of the road. The same survey reflects that 42 per cent of pedestrians would be encouraged to use public transport if the first and the last miles were covered by footpaths and safe pedestrian crossings -- basic amenities for pedestrians.1 However, these footpaths are either broken, blocked, or occupied by unauthorised car parking, leaving barely enough room to walk.

Pedestrians are advised to use zebra crossings to avoid unwanted collisions. But most drivers overlook them and stop their vehicles encroaching on these crossings, leaving no alternative for the pedestrian but to navigate through the maze of vehicles.

Fatal road accident victims largely constitute young people -- young adults in the age group of 18-45 years accounted for 66.5 per cent of victims in 2022. People in the working age group of 18-60 years account for 83.4 per cent of total road accident fatalities. Pedestrian road users were 19.5 per cent of persons killed in road accidents.2 These fatalities are mainly attributed to various reasons such as speeding vehicles, unsafe road infrastructure and unsafe vehicles.

Unsafe Roads

Dug-up roads are a common sight in Indian cities. Agencies with different responsibilities dig the roads and footpaths to install or repair the infrastructure but shy away from restoring them later, leaving the roads and footpaths with potholes and crooked passages. The first victims of such negligence are the pedestrians, who are then forced to use the carriageways, further risking their lives with potential accidents. Accountability is gravely missing on the part of these agencies.

“ Pedestrians are advised to use zebra crossings to avoid unwanted collisions. But most drivers overlook them and stop their vehicles encroaching on these crossings, leaving no alternative for the pedestrian but to navigate through the maze of vehicles. ”

Speeding Vehicles

The urge to make roads free of traffic signals has made crossing the roads more difficult for pedestrians. The main reason behind this is speeding vehicles. Speeding, even in the narrow lanes, is the new norm. Motorised travellers either speed up to cross a traffic signal before it turns red or simply jump it, making road crossings a dangerous venue for pedestrians. As per the Crime in India Report by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), 47,806 cases of hit and run were registered in the year 2022.3

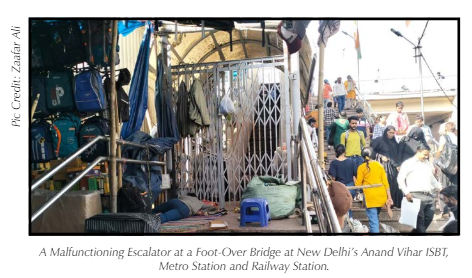

FOB: Facility/Hardship

Foot overbridges around railway stations, inter-state bus terminals and metro stations provide a safe option for pedestrians to cross roads. Despite being a safe means of crossing the roads, pedestrians avoid using FOBs. As is the case, the elderly, children, sick, differently abled, pregnant women and pedestrians carrying numerous items and bags don’t prefer FOBs. Climbing and descending stairs are more of a hardship than a facility, devoid of ramps or electronic escalators. The dependence of escalators on electricity leads to irregular maintenance, and consequently, reduced utilisation.

Subways also have steps, though they are seen as a refuge for the homeless, beggars and criminals. Post sunset, the sense of safety decreases even further. Water logging during the rainy season is another drawback in the Indian subways due to their faulty designs.

An evaluation study of the FOBs and subways in Delhi reveals their precarious conditions. As listed, Delhi has a total of 74 FOBs and 37 Subways in three zones. Among them, only 17 are equipped with lifts and 17 have escalators. The report further reveals that only nine lifts are in working order. Out of the eight faulty lifts, seven were out of order for more than a week.

Like lifts, the breakdown period of escalators also varies from one day to 1,095 days. Almost 60 per cent of the malfunctioning escalators were found to be out of operation for more than 15 days. Only about 78 per cent of FOBs have lighting arrangements.

Unlike FOBs, subways are even smaller in numbers. Merely 10 out of 37 subways are equipped with ramps. Only one is equipped with a lift and not even a single one is equipped with an escalator. Security guards are provided in only 70 per cent of subways4. No wonder, these so-called amenities often become a hardship for pedestrians.

Guidelines for Pedestrian Crossings

Indian Road Congress (IRC) 2012 set down clear guidelines on how at-grade crossings should be designed. As recommended, urban streets should have a pedestrian crossing every 80-150 metres in commercial areas and every 80-250 metres in residential areas. These crossings should be at street level and marked with paint. Wherever possible, crossings should be raised to the level of the adjoining footpaths on both sides so that pedestrians can cross the street without having to step up or down. There should be pedestrian refuges at the median to enable them to cross the road safely. Crossings, where the probability of collision is high, should have exclusive signals that are long enough for pedestrians to safely cross the road.5

FOBs and Skywalks

IRC has also set guidelines for the construction of subways, skywalks and FOBs. It emphasises the fact that skywalks are not a replacement for footpaths. Pedestrians will require footpaths to access shops and other buildings at street level. Skywalks should not be a standalone facility but integrated with entry or exit of the building at the same level for seamless and convenient walking. They should be well-shaded with a roof to provide protection from heat and rain. They should be well-lit and visually transparent to improve passive Patrolling should be done especially during late evenings. Lifts, escalators and tactile pavers should be provided for access to people with disabilities and the elderly. The sub-structure of an elevated skywalk should not hinder the pedestrian movement on the footpath below. Seating may be provided along the skywalk corridor6.

Pedestrians’ Behaviour

It is common for pedestrians to adopt risky behaviours such as jaywalking. They jump over the railings dividing the road lanes, or rush to the undesignated crossing points, disrupting the flow of traffic. Seeking shorter routes to cross the road and a lack of maintenance and safety provisions in FOBs and subways are among some of the reasons for the risky behaviour. An opinion survey conducted by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) similarly showed that “90 per cent of walkers and cyclists prefer crossing on the ground as foot overbridges and subways increase the distance and are inconvenient”.7 The absence of signals makes pedestrians act independently, resulting in rash and erratic risk-taking behaviour. The variability in the speeds of all categories of vehicles has increased after the construction of grade separators, while the waiting time of pedestrians at the starting point of a crossing has also increased. The correlation between waiting times and gaps acceptable by pedestrians shows that after a certain period of waiting, pedestrians become impatient and seek out even small gaps in the vehicular flow to cross the road.8

Lack of Political Will

Complete Bicycle Master Plans for Delhi, Chennai, and Pune were also presented at many meetings. Disappointingly, nearly 40 years later, no Indian city has any meaningful semblance of a network of pedestrian or bicycle-friendly infrastructure.9 The smart cities mission has come up with pedestrian-friendly roads and crossings. This project has announced the construction of 100 smart cities across the country. Unfortunately, the solution to a city-wide problem is yet to take place.

Way Ahead

The FOBs and subways are the by-products of policies rendering free flow of traffic by making roads signal-free. This further exacerbates the risk. In desired road planning for cities, an inverse pyramid comes into play where private vehicles are at the bottom and pedestrians remain on the top. However, the reality of the roads paints exactly the opposite picture. Subways and FOBs should be the last resort in the planning and development of urban infrastructure because these facilities are not only costly and intrusive, they deny universal access to those who prefer to commute on foot. However, for at-grade crossings to be effective in serving pedestrians, a change in mindset is necessary10.

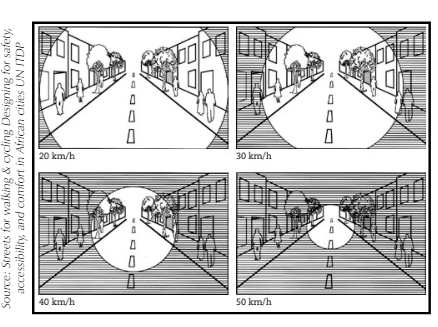

Careful enquiries into the needs of pedestrians can make crossing roads safer and easier. Minor steps in the policy can bring drastic changes, the first of which is to install speed calming measures.

“In desired road planning for cities, an inverse pyramid comes into play where private vehicles are at the bottom and pedestrians remain on the top. However, the reality of the roads paints exactly the opposite picture.”

Speed Calming Measures

Apart from installing pedestrian traffic signals at the crossings, other measures need to be looked at. To ensure safety, formal crossings should be signalised or should be constructed as tabletop crossings with ramps for vehicles. The purpose of a tabletop crossing is to reduce vehicle speeds and also to emphasise the presence of pedestrian crossing11. City administrations in Delhi

and Chandigarh have adopted tabletop crossing around accident-prone areas12, 13. Minor intersections in neighbourhood premises, where small-scale residential streets meet each other, should reinforce vehicles travelling at low speeds. These intersections should be redesigned to invite safe use and easy crossing for all users, including children walking to school and senior residents living their daily routines. Mini roundabouts, narrow lanes at crossings and road humps are an ideal treatment for unsignalised intersections of small-scale streets. They have been shown to increase safety at intersections, reducing vehicle speeds and minimising the points of conflict. In this type of intersection, motorists must yield to pedestrians.

Pedestrian crossings should be marked to clarify where pedestrians should cross and that they have priority14. These measures further increase the gaps between the vehicles facilitating pedestrians to change the side of the road.

Sensitisation of Motorised Road Users

Imposing heavy monetary penalties is one way to discipline motorised road users. Traffic signals equipped with CCTVs can be of use to take strict action against non-compliance. Apart from monetary penalties, the authorities must also undertake an awareness campaign to sensitise the drivers about the pedestrians’ needs and rights. It must be kept in the focus as an ultimate goal. Every motorised road user has to remember that in the end, he or she is a pedestrian too.

Endnotes

1. Soman, A., Kaur, H., & Ganesan, K. (2019). How urban India moves: Sustainable mobility and citizen preferences. Council on Energy, Environment and Water. 2. Ministry of Road Transport and Highways. (2022). Road Accidents in India 2022. Ministry of Road Transport and Highways. Retrieved Feb 18, 2024, from https://bit.ly/3JkvJIq 3. National Crime Records Bureau. (2022). Crime In India 2022. National Crime Records Bureau. Retrieved Feb 22, 2024, from https://bit.ly/4aZM7cZ 4. CENTRE FOR GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH PRIVATE LIMITED. (2018, November 7). EVALUATION STUDY OF FOOT OVER BRIDGES & SUBWAYS IN DELHI. Planning Department. Retrieved Feb 12, 2024, from https://bit.ly/4d52abi 5. Indian Road Congress 2012 6. Ibid. 7. Samajdar, P. (2014, June 23). Delhi tops the country in fatal road accidents and in number of pedestrians and cyclists falling victim, says new CSE assessment. Centre for Science and Environment. Retrieved Jan 18, 2024, from https://bit.ly/4aR3VHu 8. Tiwari, G. (2022, June 15). Walking in Indian Cities – A Daily Agony for Millions. The Hindu Centre. Retrieved Jan 18, 2024, from https://bit.ly/4aXWX3o 9. Ibid. 10 Ibid. 11 Jani, A. (2013, Nov). Footpath design. ITDP India. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://bit.ly/3vVAAN6 12 Victor, H. (2023, Jan 7). Tabletop pedestrian crossings coming up at three more traffic lights in Chandigarh. Hindustan Times. Retrieved Feb 28, 2024, from https://bit.ly/3Q8wVCe 13 Checchi, E., & Cognetti, G. (2021, Jul 3). Delhi’s first pedestrian-friendly scramble crossing at Red Fort likely to open by July 15. Times of India. Retrieved Feb 14, 2024, from https://bit.ly/3JmdN07 14 Global Designing Cities Initiatives, NACTO, & ISLAND PRESS. (2016). Global Street Design Guide. Global Designing Cities Initiative. Retrieved Feb 10, 2024, from https://bit.ly/49JND1X

NEXT »

Pune Experience of Traffic Gridlocks >>