How Safe are the Electronic Voting Machines?

Doubts Continue to Persist About the Veracity of the EVMs and the VVPAT System

Udit Singh*

Elections are an essential feature of a functioning democracy. It is through elections that citizens, the real sovereign, transfer their power to the candidate of their choice.1 Being a wellfunctioning democracy not only requires holding free and fair elections but also requires enactment of the rule of law and respect for the Constitution and its institutions. One can argue about the autonomy of India’s democratic institutions but the conduct of relatively free and fair elections has never been in doubt since Independence. Unfortunately, even this is shrouded in doubt today.2

One such concern is about the availability of a level playing field to all political parties participating in the elections. Several civil society organisations, including Common Cause, have approached the Supreme

The EVM has been often viewed with mistrust and claims have been made by political parties and other stakeholders that it could be hacked or tampered with.

Court with PILs to ensure that such a level-field is provided to all candidates and parties and the due process of law is followed during the elections. Some of these PILs include those raising the validity of the electoral bonds scheme3 , contempt petition for directions to SBI to disclose electoral bonds data4 , plea challenging Election Commissioners Act5 , 100 per cent EVM votes with VVPAT verification6 , uploading of Form 17C to disclose absolute voter turnout7 and petition for SIT investigation in electoral bonds scam8 .

India recently concluded elections to the 18th Lok Sabha. Among the most important issues raised by the Opposition, apart from those of corruption, unemployment and the lack of welfare schemes, was the matter of the integrity of the voting system, including the possibility of tempering of the Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs), Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trails (VVPAT) and the disclosure of the voter turnout data by the Election Commission of India (ECI).

Since its introduction in the 2004 Lok Sabha elections, the EVM has been often viewed with mistrust and claims have been made by political parties and other stakeholders that it could be hacked or tampered with.9 There is considerable doubt about the integrity of the EVMs used by the ECI and the verifiability of compliance with democratic principles. This has inevitably generated disquiet during the elections, especially during the 2019 parliamentary elections.10 However, it is also true that the parties tend to complain about the veracity of the polling process when they are in the Opposition, and this includes both the major parties, the Congress and the BJP

Soon after the declaration of 2024 Lok Sabha election results, Prime Minister Narendra Modi took a dig at the opposition INDIA bloc, asking if the EVM were ‘dead or alive’. He further alleged that the Opposition tried to blame the EVMs and thus weaken the ECI.11

However, one prominent Opposition leader, Akhilesh Yadav of the Samajwadi Party (SP), said while speaking on the Motion of Thanks to President’s Address: “Even if I win all 80 seats in Uttar Pradesh, I still won’t have any faith in EVMs.”12 Obviously, doubts still persist about the veracity of the electronic voting system in India.

History of EVM in India

EVM was first conceived in 1977. Two years later, in 1979, its prototype was developed by the Electronics Corporation of India Ltd. (ECIL), Hyderabad, a PSU under the Department of Atomic Energy. It was demonstrated by the ECI before the representatives of political parties on August 6, 1980.13

On May 19, 1982, EVM was first used by the ECI in 50 polling stations for election to No. 70 Parur assembly constituency in Kerala. Voting through EVM was done in pursuance of the direction issued by the ECI under Article 324 of the Constitution, by virtue of a notification published in the Kerala Gazette on May 13, 1982. However, prior to issuing the notification, the Commission had sought sanction of the Government of India, which was refused. Thus, the said use of EVM and election of the returned candidate was challenged in A.C. Jose v. Sivan Pillai14, wherein the Supreme Court held that ECI’s order regarding casting of ballot by machines in some of the polling stations was without jurisdiction. As a result, the election of the returned candidate with respect to the 50 polling stations where the EVMs were used was set aside.

The law was amended by Parliament in December 1988 and a new Section 61A was

The parties tend to complain about the veracity of the polling process when they are in the Opposition, and this includes both the major parties, the Congress and the BJP

included in the Representation of the People Act 1951, thereby empowering the ECI to use EVM. The amendment came into force on March 15, 1989.

In 1998, EVMs were used in 16 legislative assembly constituencies across three states of Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Delhi.

The use of EVMs further expanded in 1999 to 46 parliamentary constituencies, and later, in February 2000, EVMs were used in 45 assembly constituencies in Haryana state polls. In 2001, the assembly elections in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Puducherry and West Bengal were completely conducted using EVMs. All state assembly elections thereafter witnessed the use of EVMs.

Finally, in 2004, the EVMs were used in all 543 parliamentary constituencies for elections to the 14th Lok Sabha. On August 14, 2013, the amended conduct of Election Rules, 1961, were notified by which VVPAT was introduced. They were first used in the by-election for 51-Noksen assembly seat in Nagaland.

Features of an EVM

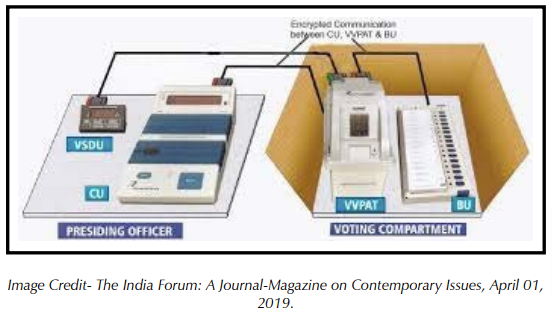

An EVM consists of two Units – a Control Unit and a Balloting Unit – joined by a five-meter cable. The Control Unit is placed with the Presiding Officer or a Polling Officer and the Balloting Unit is placed inside the voting compartment. Instead of issuing a ballot paper, the Polling Officer in-charge of the Control Unit releases a ballot by pressing the Ballot Button on the Control Unit. This enables the voter to cast his vote by pressing the blue button on the Balloting Unit against the candidate and symbol of his choice.15

The Control Unit is connected to the VVPAT printer, which is then connected to the Balloting Unit. The VVPAT printer and the Balloting Unit are kept in the voter booth. The VVPAT Status Display Unit (VSDU) is kept with the Presiding Officer and displays the status of the VVPAT printer. These different components authenticate each other using digital certificates. The system is designed to stop functioning if paired with unauthorised components.

The communication between components is encrypted. It is a stand-alone system with supposedly no external communication channels, either wired or through radio. It only has designated interfaces for input and output of data according to specific protocols. As per the ECI mandate, it should be stand-alone, i.e., not computer-controlled and ‘onetime programmable’ (OTP).

Is Hacking Possible?

One of the major concerns about EVM is that it can be hacked. In 2017, the ECI had thrown a challenge to the political parties, asking them to crack its EVMs.16 The Citizens’ Commission on Elections’ (CCE) Report on EVMs and VVPAT observed that the onus should be on the ECI and their experts to convince people beyond doubt that their design is secure, rather than illogically claiming it to be secure because the system has not yet been hacked. That is not how computer security is conventionally defined.

The report further noted that testing can usually detect malfunctioning of an equipment but is known to be inadequate for detection of backdoor Trojan attacks, simply because the possibilities are too many. An EVM system composed of its various components can exist in one of a very large number of internal states, which, almost surely, is an exponential function of the configuration parameters. Examination of such large systems is an intractable problem, which often compels the examiners to rely on weaker forms of verification such as quality assurance (QA) methods -- for instance, testing. The report further highlighted the possibilities of side-channel attacks and raised doubt over the OTP aspect of the EVM.

Some scholars have raised concern over the VVPAT system too. The VVPAT protocol should be to allow voters to approve the VVPAT slip before the vote is cast and provide an option to cancel their vote if they think there is a discrepancy.

The long-time window-- over the cycle of design, implementation, manufacture, testing, maintenance, storage and deployment—may provide ample opportunities for insiders or criminals to attempt other means of access. There is an overwhelming requirement of trust on such custody chains; such (often implicit) assumptions of trust in various mechanisms make the election process unverifiable.

Some scholars have raised concern over the VVPAT system too. The VVPAT protocol should be to allow voters to approve the VVPAT slip before the vote is cast and provide an option to cancel their vote if they think there is a discrepancy. There is no clear protocol for dispute resolution if a voter complains that a VVPAT print-out is incorrect, as there is no non-repudiation of a cast vote.

Supreme Court Rulings

The Supreme Court and several High Courts in India have time and again dealt and delivered significant rulings on the issues related to EVM and VVPAT. The Supreme Court in PUCL v. Union of India ruled that Rules 41(2) and (3) and Rule 49-O of the Rules are ultra vires Section 128 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 and Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution to the extent they violate secrecy of voting. The Court further directed the ECI to provide NOTA button in EVMs so that the voters, who come to the polling booth and decide not to vote for any of the candidates in the fray, are able to exercise their right not to vote while maintaining their right of secrecy

The Apex Court in Subramanian Swamy v. Election Commission of India noted that “paper trail” is an indispensable requirement of free and fair elections. It was held that with an intent to have fullest transparency in the system and to restore the confidence of the voters, it is necessary to set up EVMs with VVPATs system because vote is nothing but an act of expression which has immense importance in a democratic system.

The Supreme Court in N. Chandrababu Naidu v. Union of India again ruled that the number of EVMs (random selection) that would now be subjected to verification so far as VVPAT paper trail is concerned would be 5 per assembly constituency or assembly segments in a parliamentary constituency instead of what is provided by Guideline No. 16.6, namely, one machine per assembly constituency or assembly segment in a parliamentary constituency.

Recently, the Supreme Court in Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) v. ECI & Anr. rejected the pleas seeking 100 per cent cross-verification of EVMs data with VVPAT records. ADR in its plea prayed for the following directions:

- return to the paper ballot system; or

- that the printed slip from the VVPAT machine be given to the voter to verify, and put in the ballot box, for counting; and/or

- that there should be 100 per cent counting of the VVPAT slips in addition to electronic counting by the control unit.

The Court rejected the said plea. Justice Dipankar Dutta in his judgment observed:

“Instead, a critical yet constructive approach guided by evidence and reason should be followed to make room for meaningful [inference] and to ensure the system’s credibility and effectiveness.”

However, the Court issued two important directions:

(a) That on completion of the symbol loading process in the VVPAT, undertaken

The CCE report has recommended that EVM should be redesigned to be software and hardware independent in order to be verifiable or auditable so that even if a voting machine is tampered with, it should be possible to detect so in an audit.

on or after 01.05.2024, the Symbol Loading Unit (SLU) shall be sealed and secured in containers. The candidates or their representatives shall sign the seal. The sealed containers containing the SLUs shall be kept in the strong rooms along with the EVMs at least for a period of 45 days post the declaration of results. They shall be opened and examined and dealt with as in the case of EVMs.

(b.) The burnt memory/ microcontroller in 5 per cent of the EVMs -- the Control Unit, Balloting Unit and the VVPAT, per assembly constituency/assembly segment of a parliamentary constituency -- shall be checked and verified by the team of engineers from the manufacturers of the EVMs post the announcement of the results for any tampering or modification, on a written request made by second and third runner up candidates.

In May, 2024, Common Cause and ADR again approached the Apex Court by filing an interim application in the writ petition filed by it in 2019 seeking directions to the ECI to publish booth-wise absolute numbers of voter turnout and upload the Form 17C records of votes polled on its website.

The Court, while not expressing any opinion on the merits, denied to grant any relief and adjourned the application to be heard with original writ petition, by observing that grant of relief, as claimed, would amount to grant of final relief claimed in the writ petition.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, EVM is a machine and nobody can give 100 per cent assurance that it is hackproof. Although the Apex Court has bestowed its trust on the ECI regarding the safeguard features of the EVM, but can it be said with certainty that it cannot be rigged, considering its physical access and custody chain to various stakeholders? The CCE report has recommended that EVM should be redesigned to be software and hardware independent in order to be verifiable or auditable so that even if a voting machine is tampered with, it should be possible to detect so in an audit.

The overall correctness of voting is established by the correctness of three steps: (i) ‘cast-asintended’, indicating that the voting machine has registered the vote correctly; (ii) ‘recordedas-cast’, indicating the cast vote is correctly included in the final tally; and, (iii) ‘counted as recorded’, indicating that final tally is correctly computed.36

Also, the ECI should physically verify the paper slips of the VVPATs with the number of votes in the EVM.

References

- Devasahayam, M. G. (2024, May 14). Machine’s whim versus people’s will. Frontline. https://bit.ly/4ddIX6I

- A not-so-level playing field: Our free and unfair elections. (2024, April 13). Deccan Herald https://bit.ly/4fdsgKq

- Das, A. (2024, February 14). Supreme Court Strikes Down Electoral Bonds Scheme As Unconstitutional, Asks SBI To Stop Issuing EBs. LiveLaw. https://bit.ly/3Wxu6OK

- Das, A. (2024, March 11). Supreme Court Ruling On Electoral Bond Scheme:SBI Must Disclose Details by March 12. LiveLaw. https://bit.ly/3YfcJDL

- Supreme Court Refuses To Stay Election Commissioners’ Act Dropping CJI From Selection Panel. (2024, March 21). Live Law. https://bit.ly/4cX4Pn1

- Jain, D. (2024, April 25). Supreme Court Rejects Pleas Seeking 100% EVM-VVPAT Cross Verification, Issues Directions To Seal Symbol Loading Unit. LiveLaw. https://bit.ly/3SHzzAz

- Das, A., & Jain, D. (2024, March 21). Supreme Court Refuses To Stay Election Commissioners’ Act Dropping CJI From Selection Panel. Live Law. https://bit.ly/4cX4Pn1

- Live Law Network. (2024, April 23). Plea In Supreme Court For SIT Probe Into Electoral Bonds ‘Scam’, Alleges Quid Pro Quo Between Corporates & Political Parties. Livelaw. https://bit.ly/3WwHFhz

- Mishra, S. (2024, March 31). Are EVMs credible? Here’s what ECI and former commissioners told THE WEEK. The Week. Retrieved May 20, 2024, from https://bit.ly/3Wfn3ZR

- Lokur, M., Habibullah, W., Hariparanthaman, Kumar, A., Banerjee, S., Philipose, P., Dayal, J., Burra, S., & Devasahayam, M. G. (2022, January 15). Citizens’ Commission on Elections’ Report on EVMs and VVPAT. Economic and Political Weekly, LVII(3), 35-41.

- “Is EVM Dead Or Alive?”: PM Modi Takes Swipe At Opposition. (2024, June 7). NDTV. Retrieved June 8, 2024, from https://bit.ly/3LwG4SG

- Sehran, S. (2024, July 02). Akhilesh Yadav’s EVM dig at Election Commission: ‘Even if I win… Don’t trust’. Hindustan Times. Retrieved July 03, 2024, from https://bit.ly/3WxVPPm

- Legal History of EVMs Inner PGE_13_09_2022.indd. (2022). Election Commission of India. Retrieved May 26, 2024, from https://bit.ly/4f8FAzL

- 1984 SCR (3) 74.

- FAQ : EVM and VVPAT. (n.d.). CEO Madhya Pradesh. Retrieved May 29, 2024, from https://bit.ly/3zVhmc7

- Election Commission dares parties to hack its EVM from June 3, sets 7 conditions. (2017, May 20). The Economic Times. Retrieved May 30, 2024, from https://bit.ly/3SHAoJF

NEXT »