Police Compliance with Legal Procedures

Views on Custody, Confessions, and Safeguards

Torture by the police occurs most often during the earliest stages of suspects being brought into custody, i.e., during and following the arrest (Human Rights Watch, 2016). While India does not have a specific torture prevention law, there are numerous legal safeguards and procedures designed to prevent custodial torture. Police need to adhere to those safeguards and procedures to uphold the rights of the accused and ensure the legality of the arrest. The Constitution of India also extends fundamental rights to arrested persons that are meant to act as shields against torture.

There are several procedural requirements to be followed by the police at the time of arrest. There are safeguards obligating the police to ensure that arrested persons have access to key actors/authorities soon after their arrest—a lawyer, doctor, and a judicial magistrate. These actors/authorities are duty-bound to ensure that the arrested person is not being tortured or being subjected to violence and/or ill-treatment in custody. Beyond the arrest, confessions made to the police are inadmissible in court as evidence based on the very principle that the police may obtain such confessions through torture, coercion, or inducement.

This article garners police’s opinions on adherence to arrest and other legal procedures and upholding the safeguards against torture. It also examines police’s views on the duration of police custody, confessions to the police and aims to understand whether the present safeguards are seen as important.

Extracts from Chapter 4 of SPIR 2025 are given below to present some of the main findings of the chapter.

Compliance With Arrest Procedures

The police respondents were asked how often, in their experience, various arrest procedures are adhered to when a person is being arrested. It is important to note that the legality of any arrest is dependent on full compliance with all of these procedures. As per this threshold, compliance is poor.

Eleven percent said that the family members are “rarely or never” informed about the arrest

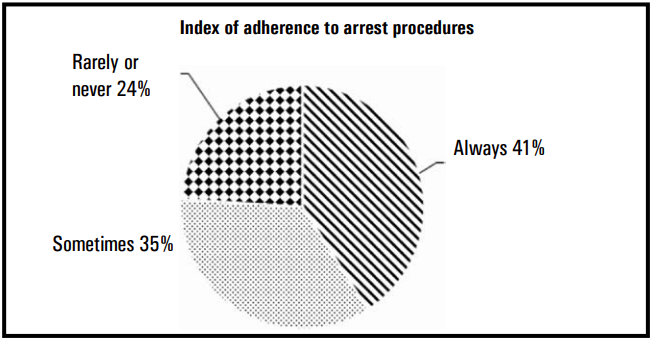

Figure 1: Only two out of five police personnel reported the arrest procedures always being adhered to when a person is being arrested

Note: All figures are in percentages. The categories of “rarely” and “never” were merged while creating the index. Please refer to Appendix 5 of the SPIR 2025 to see how the index was created.

Question asked: In your experience, how often are these procedures followed when a person is being arrested – always, sometimes, rarely, or never? : Inform them of the reasons for the arrest; Complete an arrest memo with all the required signatures; Identify yourself as a police officer with your name tag visible; Inform their family members about the arrest; Inform them that they can contact a lawyer; Complete an inspection memo; Take the arrestee to a doctor for a medical examination; Have a female police personnel present at the time of a woman’s arrest; Release the person on bail immediately at the police station in bailable offences.

(17 percent said “sometimes”, 70 percent said “always”). Twelve percent said that the arrestee is “rarely or never” taken to the doctor for a medical examination, while 70 percent said they are “always” taken. Nine percent police personnel said that the inspection memo is “rarely or never” completed, against 72 percent who said that it “always” happens. In a similar vein, nine percent of the police respondents said that arrestees are either “rarely or never” informed of the reasons for their arrest, against 72 percent who said that it “always” happens. Just 65 percent of the respondents said that they “always” identify themselves as police officers with name tags visible at the time of arrest. Further, 80 percent said that a female officer is “always” present at the time of a woman’s arrest.

It is settled in law that accused persons have a statutory right to be released on bail in bailable offences on fulfilling bail conditions (Section 478, BNSS, 2023). However, only 62 percent police respondents said that the arrested person is “always” released on bail immediately at the police station in bailable offences, while 19 percent said they are “sometimes” released, 9 percent said “rarely” and four percent said “never”.

Overall, only two out of five police personnel (41%) reported that arrest procedures are “always” followed, while 35 percent reported that they are “sometimes” adhered to. Worryingly, close to a quarter of the respondents (24%) said that the arrest procedures are “rarely” or “never” followed (Figure 1). Police personnel from Kerala report the highest likelihood of adhering to arrest procedures, with 94 percent saying that arrest procedures are “always” followed. Contrastingly, only eight percent of police personnel from Jharkhand report “always” adhering to arrest procedures.

Overall, only two out of five police personnel (41%) reported that arrest procedures are “always” followed, while 35 percent reported that they are “sometimes” adhered to

Access to External Safeguards: Lawyers, Doctors and Judicial Magistrates

On being asked how soon after an arrest, the arrested person is generally allowed to meet their lawyer, one-third of police personnel (32%) expressed the view that it is decided by the investigating officer in the case. Another 32 percent said that arrested persons are allowed to see a lawyer “immediately”. Seventeen percent said that it

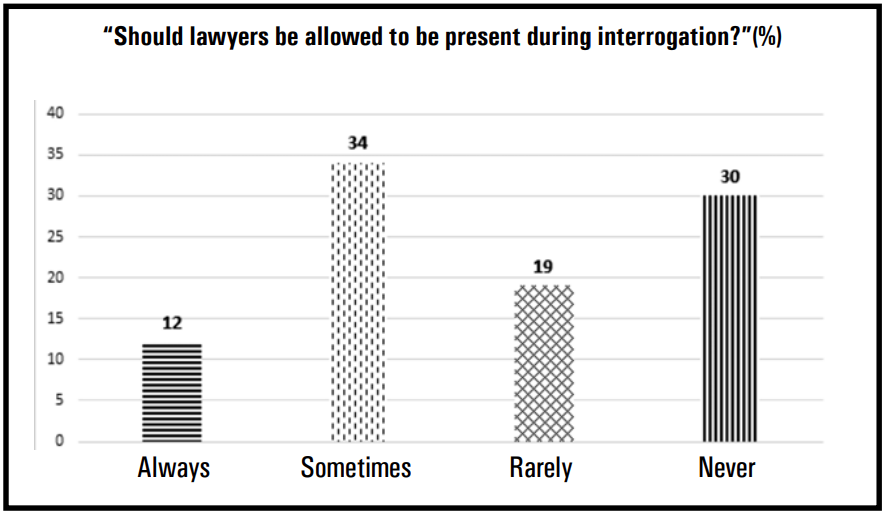

Figure 2: Thirty percent of police personnel believe that lawyers should never be allowed to be present during interrogation

Note: All figures are in percentages. Rest did not respond.

Question asked: Should lawyers be allowed to be present during interrogation – always, sometimes, rarely, or never?

is generally allowed only once the arrested person is taken to the judicial magistrate. Seven percent said that lawyers are not permitted before the person is produced before the magistrate.

The police respondents were also asked if they think that lawyers should be allowed to be present during interrogation. Only a little more than one-tenth of them (12%) said that lawyers should “always” be allowed to be present during interrogation, while only one-third of them (34%) said that lawyers can “sometimes” be allowed. Strikingly, a significant proportion of the respondents—30 percent—thought that lawyers should “never” be allowed to be present during interrogation, in complete violation of the law (Figure 2).

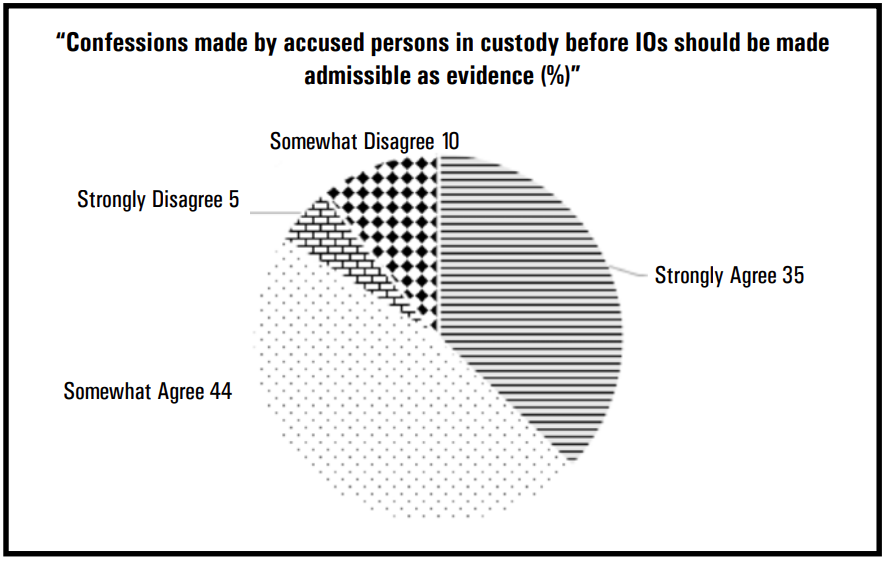

Figure 3: Four out of five police personnel believe that confessions made to the police should be admissible in court

Note: All figures are in percentages. Rest did not respond.

Question asked: “Confessions made by accused persons in custody before Investigating Officers of all ranks should be made admissible as evidence”. Do you agree or disagree with this statement.

Further, the police personnel were asked their opinion on how feasible or practical it was to take every arrested person for a medical examination. The responses of the police respondents revealed that only a little more than half of them (57%) said that it is “always” feasible to take every arrested person for a medical examination, while three in every ten (31%) also said that it is only “sometimes” possible. Cumulatively, one-tenths of the respondents even reported that it is either “rarely” (8%) or “never” (2%) possible to ensure the medical examination of every arrested person.

Presenting an arrested person before a magistrate within 24 hours of arrest is a constitutional mandate. Police personnel were asked how feasible is it to produce an arrested person before the magistrate within 24 hours of arrest. Fifty-six percent of respondents said that it is “always” feasible, 30 percent believed that it is “sometimes” feasible, and 11 percent said that it is “rarely or never” feasible. IPS officers were the least likely (39%) to believe that it is “always” feasible to produce a person before a magistrate within 24 hours of the arrest, while upper subordinate officers were the most likely (61%) to believe so.

Duration of Police Custody

In this study, the police personnel were asked for their opinions on the duration of police custody of arrested persons. While 36 percent agreed that “15 days is sufficient time for police custody of accused persons”, another 31 percent were of the opinion that “in serious offences, time in police custody should be extended beyond 15 days”. Further, 20 percent felt that “time in police custody should be extended beyond 15 days for all accused persons”. Surprisingly, seven percent also went so far as to say that “15 days is too long, it should be reduced”, which was a silent answer category.

The study also found that those officers who frequently conducted interrogations were in fact more likely to agree that the 15 days’ time period for police custody was sufficient (41%), compared to those who never conducted interrogations (25%).

Reliance on Confessions

The police and criminal justice system’s reliance on confessions has been amply documented (Lokaneeta, 2020).

This report finds that four out of five police personnel believe that confessions made before the police should be admissible in court, with 35 percent respondents “strongly agreeing” and 44 percent “somewhat agreeing” (Figure 3). The centrality of confessions for the police was again reinforced when 70 percent of police personnel reported that confessions made by the accused persons are “very important” in cracking a case, while 21 percent said that they are “somewhat important”.

The police, rather than facilitating the safeguards and upholding the rights of the accused, prefer wide discretion during arrest and interrogation

Conclusion

This chapter brings to light the police’s lack of compliance with constitutional and legal safeguards at the time of arrest and interrogation, as reported by police personnel themselves. It also draws attention to the police’s reliance on confessions despite clear legal provisions regarding the inadmissibility of confessions in court. The failure to comply with procedures, as well as dependence on confessions, leaves scope for police to use torture against accused persons.

Seen together, these practices and views signal police propensities towards unbridled powers for coercive actions. This chapter shows that the police, rather than facilitating the safeguards and upholding the rights of the accused, prefer wide discretion during arrest and interrogation. The use of such discretion goes against established legal procedures and also paves the way for unbridled use of illegal force and torture in police custody.

The legality of any arrest is dependent on full compliance with all the arrest procedures. As per this threshold, compliance is poor.

References

Human Rights Watch. (2016). Bound by Brotherhood: India’s Failure to End Killings in Police Custody. pp. 50-52

Lokaneeta, J. (2020). The Truth Machines: Policing, Violence and Scientific Interrogations in India. University of Michigan Press. pp. 141-152.

NEXT »