Police Torture: Where are the Safeguards?

Excerpts of Speeches at the Launch Event

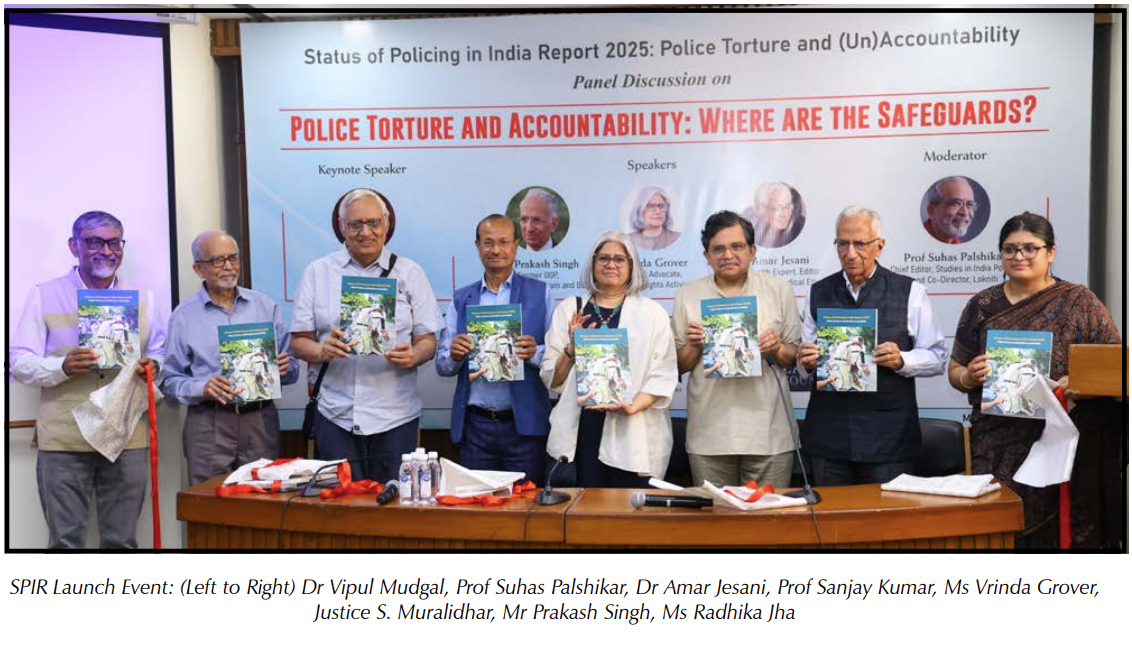

The SPIR 2025 was launched on March 26 at an impressive function at the India International Centre, New Delhi. The event was attended by lawyers, activists, students, former civil servants and police officers. After brief introductions by the Director of Common Cause Dr Vipul Mudgal, and the co-Director of the Lokniti programme, Prof Sanjay Kumar, the findings of the report were presented by Ms Radhika Jha, who leads the Common Cause chapter on police accountability.

The event featured a panel discussion titled “Police Torture and Accountability: Where are the Safeguards? ” The panellists were Mr Prakash Singh, former DGP of UP, Assam, and BSF; Dr Amar Jesani, a public health expert and Editor of the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics; and Supreme Court lawyer and activist, Ms Vrinda Grover. The meeting ended with a Keynote address delivered by Justice S. Muralidhar, former Chief Justice of the Odisha High Court. A recording of the event is available at the Common Cause YouTube Channel. Edited excerpts of the speeches are given in the following pages.

Please Scan QR Code to access recording of the event.

YouTube Link to access the recording of the event:

Mr. Prakash Singh

It [the Report] is a painful reading for me because it exposes the weaknesses of the police.

I need hardly say that all is not well with the police, and that is why I have been campaigning for police reforms for more than three decades since my retirement. Not much has been achieved, but yes, we have made a dent. We have brought this issue into the public domain, and people are now talking about it and debating it. I would like to thank Common Cause for the immense interest they have taken in various aspects of police functioning by bringing out reports almost every two years on different aspects of police work.

The Other Side of Policing: Understanding Force and Excesses

I said all is not well with the police, but even then, I think things have to be viewed in a perspective that helps you understand two things — a.) The other side of the picture, and b.) Why do these things happen? Why are there excesses by the police? Why is there brutal use of force by the police?

Firstly, we are talking mostly about torture. But what is the definition of torture? Nobody is clear about it in India. The UN Convention does define torture, but in India, there has been no official definition. Would giving a slap amount to torture? I don’t think so. Torture is much more serious — there has to be grievous hurt, there has to be solitary confinement, there has to be waterboarding, there has to be a threat of death — things like that, very, very serious matters. So, torture is to be distinguished from a lot of other things.

I would say tough methods need to be distinguished from torture… When you are dealing with hardened criminals…you have to be firm, you have to be tough. Now where is the border line and where do you cross it, that’s a different matter. When does tough line degenerate into torture, that has to be understood. You need to adopt tough methods without talking of torture.

The report itself talks of police officers saying that great emphasis needs to be given to training in human rights. Seventy-nine percent of them [surveyed police personnel] are giving importance to human rights. Seventy percent say that we need to educate our force about the prevention of torture. Again, 79 percent say that interrogation should be evidence-based. So, under all these three heads, the percentage is above 70 — of policemen supporting human rights, supporting the prevention of torture, and supporting evidence-based interrogation.

So this is the other side of the picture. I mean, as I said, the glass is 70 percent full. Only 25 percent is contrary to expectations.

Tough methods need to be distinguished from torture… When you are dealing with hardened criminals… you have to be firm, you have to be tough. Now where is the border line and where do you cross it, that’s a different matter.

Now, there’s another crucial point — the use of force without fear of punishment. Why should there even be a debate about it? Why is the danda [police baton] given to you [the police force]? Why are rifles given to you? Why is even more sophisticated equipment coming into the force? They are to be used in certain situations. But in those situations, if you are diffident or hesitant in the use of force, then you are abdicating your duty.

A Day Without the Police

I’ll put it differently. Let’s say that tomorrow, IAS officers go on leave — nobody performs their functions. Would life be very much disturbed? Let’s say the Customs Department goes on leave — maybe there’ll be some smuggling. But can the police say, “We are on leave for 24 hours, and we will not take any action against criminals”? Can you even visualise that situation for one day?

The reason is that the fear of the police is there—and the fear of the police has to be there. If you completely remove that element of fear, then you are heading for chaos. You are heading for anarchy. You won’t be able to step out of your house and feel safe. Women, girls — they will not feel safe going out.

The police has to be — and should be — able to use force in situations that warrant the use of force. Of course, the quantum of force used should not be excessive.

There’s enormous political or public pressure for quick results that leads to excesses. There’s a lack of faith in the criminal justice system. I’m not justifying police torture, but I’m just trying to explain the circumstances under which these things happen. Lack of accountability, deficiencies in training, constraint of resources— these are the factors which contribute to this.

Police Force: A Tool to Uphold the Law

The police are meant to use force to maintain law and order. And India is a country where you have all kinds of problems — there is Naxal violence, there is Kashmir, there is violence in the entire Northeast…you have violence everywhere — caste riots, communal riots. How do you deal with them except by using force?

Of course, preventive action should be taken wherever possible. But if the use of force is inevitable and unavoidable, and when you are using that force legitimately, in the proper discharge of your duties, in a bona fide manner, you should have the assurance that you will not be punished for it. There is no question of any debate on this point.

Police Confession

The report is totally against confessions [before the police]. Why is it so? Is anyone sitting here — a lawyer, a judge, or a magistrate — more trustworthy than I am? I would like to know. I challenge that notion. The Malimath Committee, which examined reforms in the criminal justice system, clearly stated that, with certain safeguards, confessions made before a police officer should be admissible. It was all right in British India that you did not trust the police officer. But now, these are your own boys — they are the cream of the country. They come from the best families, with the best backgrounds, and they are among the most qualified people. In fact, Indian police officers are more qualified than police officers anywhere in the world.

Reasons Behind Police Torture

There’s enormous political or public pressure for quick results that leads to excesses. There’s a lack of faith in the criminal justice system. I’m not justifying police torture, but I’m just trying to explain the circumstances under which these things happen. Lack of accountability, deficiencies in training, constraint of resources—these are the factors which contribute to this. I am not justifying torture at all, and the kind of instances which have been quoted in the book are absolutely revolting. But I’m saying that the use of force has to be understood in certain circumstances, and the circumstances under which excessive force is used, need to be understood.

Dr. Amar Jesani

For a very long time in India, we have talked about deaths in police custody,

but we have not talked about torture at all. Worldwide, if you see the history, in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, after Amnesty International was formed in the early 1970s, torture became a major area of campaign internationally.

Unfortunately, in India, both the official agencies as well as the human rights organisations have neglected this whole issue of torture. As a consequence, you’ll find that there has been very little discussion about it.

Even here, what we are talking about in this report is torture in a very strong moral sense, saying that torture is bad. That’s the premise — if you read the whole report, it is very simple: torture is bad.

Well, yes, it is an ethical problem, and it’s definitely a moral issue.

Torture’s Efficacy in Crime Prevention

I think the fundamental issue that we need to ask is: Is torture actually efficacious in controlling crime or in bringing criminals and terrorists to justice? And that’s where we find no data. I have been looking for it for a very, very long time — and except for anecdotal evidence, you won’t find anything concrete.

We are worried about the conviction rate being very low in criminal cases. Why is it so? If torture were really effective — and if it were being used in every police station — then we should have a 100 percent conviction rate, right?

I remember the debate that took place in the early 2000s when narco-analysis was being used (extensively). Narco-analysis emerged as part of the broader post-9/11 response, which advocated for more “sophisticated” means of coercion. The idea was: don’t torture in a way that evokes public outrage — do it in a clinical, scientific manner.

In political science, you’ll even find certain papers discussing concepts like “liberal democratic torture.” I was reading an article on this in the British Journal of Political Science. It argued that this form of torture involves specialists — medical professionals — who inflict suffering without leaving physical signs, using medical science to extract information.

Now, if we have a truth serum, do we really need a judge like the honourable Justice sitting here? Because, apparently, if the “truth” is already out, then there’s nothing more to adjudicate. Right?

IPS officers don’t like the constables who do random beatings. Random beating is bad because you get emotionally carried away, some kind of a sadistic tendency comes out, and the person dies, and there’s a big outcry and a scandal.

You also have brain mapping and other such techniques. So, this is fundamentally one area that we need to look at: Is torture efficacious? And why have we not asked that question to the policemen in this report? They may say they do it, but do they have anything to back it up with? Any argument, any evidence, to show it has efficacy?

Why are IPS Officers the Biggest Supporters of Tortures?

The Indian Police Service officers are among the most trained and elite people, right? And I’m sure they are being trained in a very scientific manner — even when it comes to torture. One of the roles of the medical profession has historically been to provide ideas on how to conduct torture. There’s no better torturer, arguably, than a group trained to carry out scientific torture in an “efficacious” manner.

I had an experience of being in the police station and being arrested and watching how they work, and IPS officers don’t like the constables who do random beatings. Random beating is bad because you get emotionally carried away, some kind of a sadistic tendency comes out, and the person dies, and there’s a big outcry and a scandal. I remember being in the police station where the inspector, since I was in preventive detention a long time ago, was taking me around. He pointed things out, and at one point said, “This is not the way to torture.” According to him, the right way of torturing was a focused, scientific method. If done that way, he claimed, you’d get information quickly.

What I saw, though, was that you rarely get information — what you mostly get are confessions, or people being implicated by others under duress. And perhaps that explains why IPS officers, paradoxically, are among the biggest supporters of torture — not necessarily because it works, but because it’s seen as a tool of control, systematised and “rationalised.”

Doctor’s Role in Torture

I would say we need to talk more about doctors and their role. I’ve been involved with this issue since the 1980s, more at the international level, because at the national level, I found a troubling pattern. If you conduct a human rights investigation and find that a doctor neglected their duty — for example, failed to help an accused person who had been beaten and brought to the hospital — and you include that in the report, the human rights organisation will often say: “We are fighting against the police. The police are the enemy. We don’t want to make doctors the enemy, too.” So, it gets underplayed at press conferences or when things are being taken forward publicly.

But we have to remember that if we want justice and accountability, there are multiple actors involved. If the system is not made accountable at every level, we may win a few cases here and there, but we will not be able to stop torture at the ground level. In other words, prevention becomes impossible.

Now, what happens to a person who is tortured? Because of physical injuries, that person definitely comes into contact with the medical system. Either the police bring them to a hospital, or they go on their own after being released. And the doctor, in most cases, can identify that the injuries are due to torture

But there’s another aspect that often gets left out, and that’s mental health. You must have heard of PTSD — Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. This term was first used for GIs [soldiers of the US Army] returning from Vietnam, who had either engaged in or witnessed extreme violence. Similarly, people who are tortured also suffer from posttorture syndrome. I have seen survivors go to doctors months later, seeking help for mental health issues. But doctors often fail to recognise the symptoms or connect them to the torture experience.

This is why I say, whenever someone is severely tortured, they do come across the medical system somewhere, and that must be one of the key points of intervention for those fighting for accountability. Doctors must be allies in this struggle.

Torture Victims and Examination

I think you interviewed quite a few forensic experts, and their views have come through quite strongly. One, that there are not enough forensic experts available; and two, that doctors don’t really know forensic medicine. But the fact is — if you’ve done an MBBS, you are supposed to know it. Forensic medicine is a subject you are required to study.

The reality, however, is that these things are not taught properly, and that’s something we will have to overcome.

What actually happens at the ground level is this: most of the time, people who’ve been tortured or injured are not examined by forensic experts. Instead, they are seen by the practising doctors at the hospital. This could be a general practitioner or a specialist in any branch. And I think this is quite justified — it’s not just in India. You will find the same thing in the UK. A general practitioner may be doing the same kind of medical examination. So, globally too, it’s quite common for a regular doctor to perform the role of a forensic examiner.

Even with autopsies — at the level of Primary Health Centres, Community Health Centres, or District Hospitals — it is not the forensic experts conducting them. It is other doctors who carry them out, because they’re supposed to have basic knowledge of forensic medicine.

Here, I think we need to shift the focus. It’s not only about the lack of forensic experts — it is about the existing doctors not doing their job properly. That’s where the problem lies.

Ms. Vrinda Grover

We were told by the government that the [criminal] laws are being decolonised.

And therefore, three new laws have been brought in: as we know, the BNS [Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita 2023], the BNSS [Bhartiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita 2023], and the BSA [Bhartiya Sakshya Adhiniyam 2023].

One of the things that was absent from the “colonial law”, the Indian Penal Code, was the offence of torture, despite the fact that it was committed excessively by the colonial rulers and regime. One would have imagined that this was the right time to introduce torture as an offence. Its silence and omission today are very striking, and therefore compel us to ask: Why did the government not want to make torture an offence?

The Indian state signed the UN Convention Against Torture as far back as 1997. We now find ourselves in the company of a handful of states — states we do not usually like to associate ourselves with — that have only signed, but not ratified, the Convention.

We think of ourselves as belonging to a very different domain. So why has ratification not taken place? The reason, we are told, is that under the Indian Constitution, a domestic law must first be passed before ratification can follow.

This is a conversation that the Government of India has been having — both at the domestic level, including in the Indian Supreme Court, as well as at the United Nations — for a very long time.

Accountability over Reform

I don’t like the phrase “police reform.” I think the appropriate phrase is “police accountability”. It’s not an institution that needs to be reformed, it is an institution that serves the people of the country and therefore must be accountable to the law of the land. Not to the political class, but to the law of the land.

The issue of police accountability, particularly in the context of encounters, was brought into focus by democratic rights groups. The guidelines we have today in the NHRC were originally brought forward by democratic rights groups in the (undivided) Andhra Pradesh.

The importance and significance of civil society in creating mechanisms of accountability in our democracy cannot be undermined. It is groups of that kind that have actually moved various institutions, including the courts, and Common Cause does this extensively.

The definition of torture is neither a mystery nor (is) ambiguous. It is clearly defined in the UN Convention Against Torture, which states:

“Any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for purposes such as obtaining information, punishment, intimidation, or for discriminatory reasons, by or at the instigation of, or with the consent or acquiescence of, a public official.”

I don’t like the phrase “police reform.” I think the appropriate phrase is “police accountability”. It’s not an institution that needs to be reformed, it is an institution that serves the people of the country and therefore must be accountable to the law of the land. Not to the political class, but to the law of the land.

Rape as a Tool of Torture

One big gap that I do find in the report is the absence of a clear recognition that, across the world today, including in India, sexual violence, particularly rape, is a form of torture, and is recognised as such.

I’m presently on a UN Commission, and we are actually documenting, in times of armed conflict, the kinds of sexual violence — on both male and female detainees — that are taking place. We are describing it, even under international law, as a form of torture.

And I think there is a gap. It’s not being explicitly said, but if you read the report, this part is actually missed altogether. I think it’s very important to always have a gender lens when we are doing this kind of work.

Rape in custody, as we know, is already recognised as an offense — and therefore, it is not just a sexual offense. It must also be understood as a form of custodial torture.

Institutional Bias as an Enabler of Torture

We are a plural society, a society of equal citizens. We cannot have a force that is authorised by law if there is bias, and that bias is clearly showing. Not only against Muslims, but also against the poor. It has always been there, against Dalits, against Adivasis. There is enough evidence.

Perhaps those who are in positions to take corrective measures will not do so. Therefore, it becomes our responsibility. How do we initiate those measures? How do we campaign for those measures? That is what I have been doing for some time.

A case — or rather, a video — that many of you would have seen is of Faizaan, being beaten by policemen. It’s a video that went viral. The men were in police uniform, so it becomes hard to claim they weren’t doing it. Nobody else was roaming around wearing Delhi Police uniforms during the February 2020 Delhi riots.

It took us from 2020 to the end of 2024 just to get the investigation transferred to the CBI from the Crime Branch — all very elite, premier agencies.

That video went viral. What does it show? Forget the custodial killing — the boy is dead. It shows bias. Institutional bias.

Did any senior police officer in Delhi acknowledge there is a problem in the force? Why were they beating an unarmed young Muslim man, who, by their own records, did not participate in the riots? They checked every CCTV footage they could find. He didn’t pick up a stone. And had he done so, there would have been no chance for us to carry this conversation forward. So why was the Delhi Police Commissioner not alarmed? Why is it not bothering him? Is it all right for Delhi Police to beat, thrash, and illegally detain an unarmed young Muslim man?

We are a plural society, a society of equal citizens. We cannot have a force that is authorised by law if there is bias, and that bias is clearly showing. Not only against Muslims, but also against the poor. It has always been there, against Dalits, against Adivasis. There is enough evidence.

This is not just individual bias anymore. There is institutional bias in the police force — one we are refusing to acknowledge, and therefore, we don’t remedy it. We don’t correct it. But we cannot run away from it.

Targeting Torture in the Name of Crime Control

In this country, there is undeniable anxiety about crime. All of us feel it — in our homes, for our children, for our daughters. Crime is on the rise. And with increasing impoverishment and unemployment, crime will continue to rise.

So, what are we going to do?

Are we going to keep eliminating people, torturing people, locking them away, and handing out harsher punishments?

This is not just individual bias anymore. There is institutional bias in the police force — one we are refusing to acknowledge, and therefore, we don’t remedy it. We don’t correct it. But we cannot run away from it.

Has that reduced crime?

Who, then, is preying on our anxieties? And who is accumulating more power in this entire process? That is something we need to think about very seriously.

There is a very insidious — and yet relentless — process underway:

A narrative that says, “Courts are useless, courts take time, let’s get on with it, let’s get rid of the legal process — it’s for our own benefit.”

That is exactly what a police state thrives on. And that’s what the police want us to believe. But ask yourself: Who is defying the law in this country?

And who is the police beating?

We all read the newspapers. We see the visuals. We walk around our cities. I’ve witnessed it — even in 1984. I’ve always lived in this city. The police did nothing when Sikh homes were being burnt. So this is not about any one regime.

Today, ask: Who is being lynched? Who is being harassed? Whose homes are being raided?

Whose shops are being burnt?

The police? They are bystanders. They have the force, they have the authority — but they will not use it. These are the difficult truths we must reckon with. And torture, today, is no longer random. It is targeted torture. And that is what we need to start asking tough questions about.

NEXT »