Growing Concerns in Prisons

Where are Prison Reforms?

Growing Concerns and Challenges

The landscape of prison reform in India is marked by a constant stream of directions from the Supreme Court, high courts, and government circulars. These cover issues ranging from overcrowding and poor living conditions to deaths in custody, the treatment of women and children inside prisons, and the need for rehabilitation services. Yet despite this volume of guidance, the absence of clear statutory policy that firmly shifts the philosophy of incarceration from retribution to rehabilitation has meant little substantive change.

The 2016 Model Prison Manual was intended to modernise prison administration, but in practice, everyday functioning continues to be guided by the colonial-era Prisons Act of 1894. This outdated legal framework, combined with entrenched security-first mindsets, dilapidated infrastructure, and chronic financial shortfalls, has prevented prisons from evolving into rehabilitative institutions.

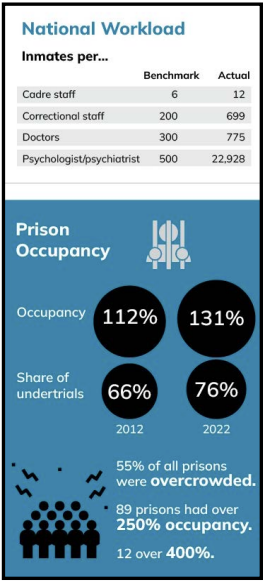

Between 2012 and 2022, prison populations rose sharply from 3.8 lakh to 5.7 lakh. Occupancy rates climbed from 112 per cent to 131 per cent, and the proportion of undertrials increased from 66 per cent to 76 per cent. These trends highlight the growing strain on prison systems and the failure to address structural weaknesses.

Infrastructure

Occupancy rates: Overcrowding remains the defining feature of Indian prisons. In 2020, 48 per cent of prisons were overcrowded; by 2022, this had risen to 55 per cent. Alarmingly, 12 prisons recorded occupancy rates above 400 per cent. Since 2021, 16 states and six UTs reported rising occupancy, with Mizoram (79% to 116%), Chandigarh (80% to 107%) and Himachal Pradesh (75% to 101%) showing the steepest increases. The largest decreases were registered by Sikkim (167% to 149%), Jharkhand (121% to 111%), and Odisha (99% to 83%).

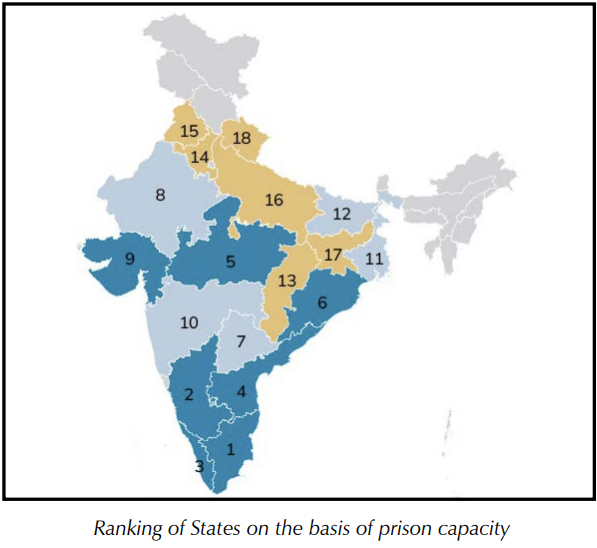

Nationally, prison housing capacity grew by 27 per cent over the decade, but this has not kept pace with demand. In 2012, 17 states and UTs had overcrowded prisons; by 2022, the number had risen to 25.

Share of Undertrial Prisoners: Much of the overcrowding is driven by ‘undertrials’, i.e., prisoners awaiting investigation or trial. Their proportion had risen from 66 per cent in 2012 to 76 per cent in 2022. Ninety per cent of prisoners in Delhi are undertrials. Amongst larger states, Bihar reports the highest share among large states at 89 per cent, followed by Odisha at 85 per cent. Tamil Nadu and Madhya Pradesh fare better, with 55 per cent and 61 per cent, respectively.

In 2024, the Supreme Court suggested open prisons as a partial solution. Seventeen states now have 91 open prisons, with Rajasthan alone accounting for 41. Eligible convicts must have served minimum sentences and demonstrated good behaviour.

Period of detention: On an average, undertrials are spending more time than ever before in pre-trial detention. By 2022, 11,448 had been detained for more than five years—up from 5,011 in 2019 and 2,028 in 2012. Uttar Pradesh alone accounted for nearly 40 per cent of these long-term undertrials. Nationally, 22 per cent of undertrials spent one to three years incarcerated, a proportion that has risen steadily across most states.

Human Resources and Workload

Staff shortages remain acute. In 2022, most states/UTs had one in 4 posts vacant. At the officer level, 11 states/UTs recorded over 40 per cent vacancies, with Uttarakhand recording the highest at 69 per cent. Nationally, cadre staff vacancies, including warders and prison guards have hovered at around 28 per cent for a decade. Jharkhand consistently reported vacancies above 65 per cent. Only Tamil Nadu (7%) and Arunachal Pradesh (2%) kept vacancies in single digits.

Correctional staff: Correctional staff comprise of probation officers, social workers and psychologists. Over the last decade their vacancies have remained at around 45 per cent. To meet the benchmark set by the Model Prison Manual (2016)—one correctional staff for every 200 prisoners—there need to be 2,866 correctional officers across the country; in reality, there are only 820.

Medical Staff: Medical staffing is equally inadequate. Between 2012 and 2022, sanctioned posts for doctors rose from 1,052 to 1,290, but actual strength increased only from 618 to 740. Vacancies remained around 41 per cent. The benchmark is one doctor per 300 prisoners, but the reality is one per 775. Only Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, and Meghalaya were able to meet the benchmark; most states fall short.

Diversity

The number of women prisoners rose by 40 per cent between 2012 and 2022, but female staff representation remains low. Women comprise just 13 per cent of prison staff, up from 8 per cent a decade earlier. Their staff numbers fell slightly from 8,881 to 8,674, with 90 per cent of women employed at the non-gazetted level.

Budgets

Sanctioned budgets for prisons rose from Rs. 3,275 crore in 2012 to Rs. 8,725 crore in 2022. Twentythree states/UTs recorded more than 90 per cent utilisation of their allocated budgets, with Tamil Nadu, Himachal and Arunachal Pradesh achieving full utilisation.

Spend per inmate: Nationally, India spends Rs. 121/day per inmate. The three highest spending states were Andhra Pradesh (Rs. 733), Haryana (Rs. 437), and Delhi (Rs. 407). The lowest spends were Mizoram (Rs. 5), Maharashtra (Rs. 47), and Punjab (Rs. 49).

While the philosophy of incarceration has, on paper, moved from retributive to rehabilitative, fiscally rehabilitation seems a distant dream. Overall, only 0.13 per cent of total expenditure was used for vocational and educational facilities and only 0.27 per cent was spent on welfare activities. Chandigarh spent 10.6 per cent on vocational and educational facilities, the highest nationally; and West Bengal spent 3.5 per cent on welfare activities. Thirteen states record no expenditure on either vocational, educational or welfare activities in 2022.

NEXT »